MY GRANDFATHER’S LAST CHRISTMAS gifts to me came early, sometime in mid-summer of the year when I was four. They were simple gifts. A stuffed lion and a bear, but they were expensive gifts for him to give for no apparent reason other than I was his grandson — and that he loved me.

It was neither Christmas nor my birthday. And he was a poor, broken down old miner with bum legs but a proud heart that shared a chest with a pair of polluted lungs, the miner’s hazard. I had been in the hospital a long time that summer, and he stayed with me after the first bad night when I had been alone and frightened.

The nuns, with tall white habits that looked like sailboat spinnakers on a sea of black, came that night to feed me intravenously. I’d resisted and I cried. They had finally used a wooden pallet to which they bound my legs and arms and then stuck me with those needles.

My grandfather came the next day, bringing me the two stuffed animals. One of them would have done. The lion. The old man had long told me stories about the lions. Something about them fascinated him, maybe their masculinity, their machismo. I was afraid of the nights and afraid of the needles I had to have each day, but he would be there telling me about the lions.

“Think of the lions, son,” he would tell me. “Remember the lions. The lions in your dreams will protect you.”

I would think about the lions and about my grandfather, and I was safe.

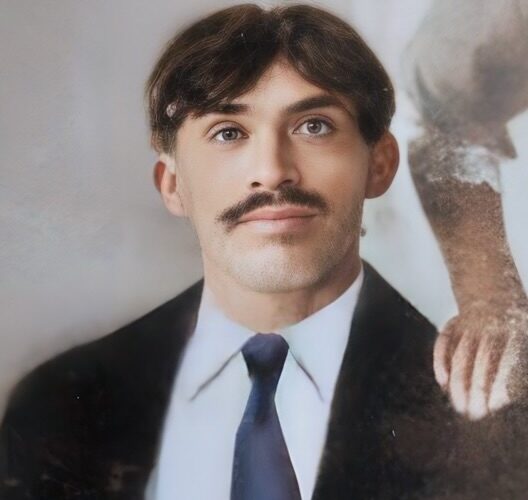

My grandfather was a fine old man, his walk a shuffle. He limped on bad legs braced in black ankle-high shoes that never laced to the top. He always dressed in pin-stripe navy pants, supported by suspenders, a starched white shirt, a vest, and a white gold pocket watch.

“Este reloj cuenta la vida de nuestra familia” — “This watch tells our family’s story,” he would tell his friends.

Many years ago, when he was barely more than a boy himself, his father had given him the watch, he said, and he, in turn, one day would give that watch to me.

That day, unfortunately, would never be. One day, while we walked the streets of the small barrio near the Brazos River where the old man lived, a gang of pachucos – Mexican thugs – surrounded us. He tried beating them away with his cane, which they stole along with the pocket watch.

“They took your watch!” I cried as we watched the pachucos flee up the street. “They took your watch!”

“The watch is worthless to them,” he said, checking to make sure that I was okay

“But it was your watch,” I said. “Your grandfather’s watch. You were going to give that watch to me.”

“Sometimes,” he said, “we can’t have what is ours. You have to learn to be a man then.”

I looked up at him. He, too, was crying.

The watch was never mentioned after that. It would not pass from him to me, nor would a lot of other things. The chain was broken. And that summer in the hospital, he almost seemed apologetic, as if he wished that he had more to give.

My two stuffed animals had been enough.

“Think of them as this year’s Christmas,” he said.

“But it’s not Christmas yet, grandfather,” I said. “That’s still a long way away.”

He knew, of course, and I kissed his stubbly face, smelling rosewater and talc, hearing the heavy breathing struggling in his chest.

The last time I saw my grandfather was two months later. Not December, but early autumn of that year. He was in the hospital where he lay sedated and unconscious. A clear plastic oxygen mask covered his nose and mouth, and two needles with long thin tubes stuck out from an arm.

I wanted to stay, as he had with me, but my dad said I could not. My stuffed lion, however, could.

I left it at his bedside. To protect him.

A few days later he was dead. I cried much of that afternoon and again that Sunday when they buried him. I had the stuffed lion with me and, as I strutted past him at the cemetery for the final time, I stopped and looked at him once more.

A gift. I wished I had a Christmas gift to give him as he had given me.

I saw his face and hoped that he was dreaming. Then I realized that I had an answer for my wish.

I placed my lion near his hands across the vest at the place where the white gold pocket watch once had been.

Then I walked on past, thinking of the lions and of a Christmas that would never come again.

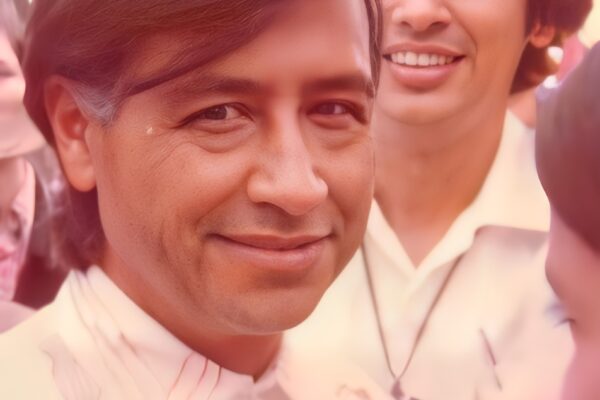

Tony Castro, the former award winning Los Angeles columnist and author of CHICANO POWER (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is an editor-at-large with the LA Independent. CHICANO POWER will be re-issued in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.