The national tragedy of November 22, 1963, affected all of us in different ways. For me, it intensified my childhood dream of wanting to write and later of wanting to report the news.

By TONY CASTRO

IF YOU ARE A TEXAN, as I am, November 22, 1963, always brings back a tearful rush of memories of one of American history’s worst moments that took place so close to home. If you grew up in Dallas or anywhere close to Big D, it also revives a sad recollection, like you would have in remembering the passing of a beloved close family member.

That Friday morning was already a difficult day. All morning long, I regretted not having ditched school. I was going to, but my parents threatened to ground me if I did. I was 16 years old, and I had to pass up hearing the president of the United States deliver a speech in person at a luncheon in Dallas, which my Uncle Jesse was attending as a guest of prominent Dallas attorney Adelfa Callejo.

Maybe that in itself was the problem. I had spent much of the last two summers and numerous weekends in Dallas at my uncle’s home, often in the company of Mrs. Callejo who was the attorney for my uncle’s aluminum siding company that had made him, if not “Dallas rich,” at least just rich enough to be luxuriously comfortable. My parents, especially my mother, didn’t like that arrangement. I never understood why, and it would take me years to figure out.

So I didn’t take the Greyhound bus to Dallas that morning. I took it late that afternoon, after all the numbing heartbreaking news that we all learned about shortly after lunch. The one-way student ticket from Waco to Dallas was $3.75, a trip I had made so often in the past that I had become more familiar with downtown Dallas than my uncle.

Arriving just before sunset, I walked the five blocks from the Dallas bus station to Dealey Plaza to watch the last glimpse of daylight disappear behind the triple underpass through which the presidential limousine had sped away at noon after the shooting.

An eerie silence had quieted the usual loud bustle around Dealey Plaza. Yet it was packed just the same with mourners carrying themselves with the solemnity you would expect at high Mass.

At most you heard murmurs drowned out by the early evening traffic and the noise created by television crews filming the growing memorial of flowers covering the incline from Elm Street upward toward the Texas School Book Depository.

Even in the evening, people on the street kept pointing up toward the depository, and the sixth-floor window that radio news kept reporting to have been where the assassin had fired downward and killed President Kennedy. Two uniformed Dallas police officers now stood guard at the door.

Other mourners also pointed to an imaginary spot somewhere in the middle of Elm Street, presumably guessing at the location on the road where the president had been shot. Nearby, a teenage girl was talking to whomever would listen about what she had seen on the television news just minutes earlier.

“Mrs. Kennedy was crawling over the trunk of the limousine trying to retrieve a piece of the president’s skull,” she kept repeating.

Everyone seemed to ignore her.

“No one wants to hear that,” one woman said, turning away.

The temperature had dropped 20 degrees at least, it seemed, since the sun set. I began walking east toward the Dallas Times Herald building two blocks away. It was Friday night, and I knew that my friend and mentor Harold Ratliff, the Dallas bureau sports editor of The Associated Press and the foremost expert of Texas high school football, would be there. Friday night lights football, after all, lives on, national tragedy notwithstanding.

The AP had its Dallas office at the Dallas Times Herald building next door to the afternoon newspaper’s own newsroom. I had been there numerous times. I was Harold’s stringer in Central Texas, a job I’d gotten two years earlier, answering his advertisement for an “industrious high school journalism senior to be a wire service intern and stringer while earning money for college.”

I hadn’t answered the ad in writing. I had shown up in person pretending to be that college-bound senior in my lucky three-piece pinstriped navy suit that made me look anything but 14 years old. Harold hired me and gave me a $50 advance.

Now, here I was, on the night of perhaps the worst tragedy in American history, with a front row seat, watching how the news was being gathered on the assassination of a president that would win a Pulitzer Prize for the Dallas Times Herald.

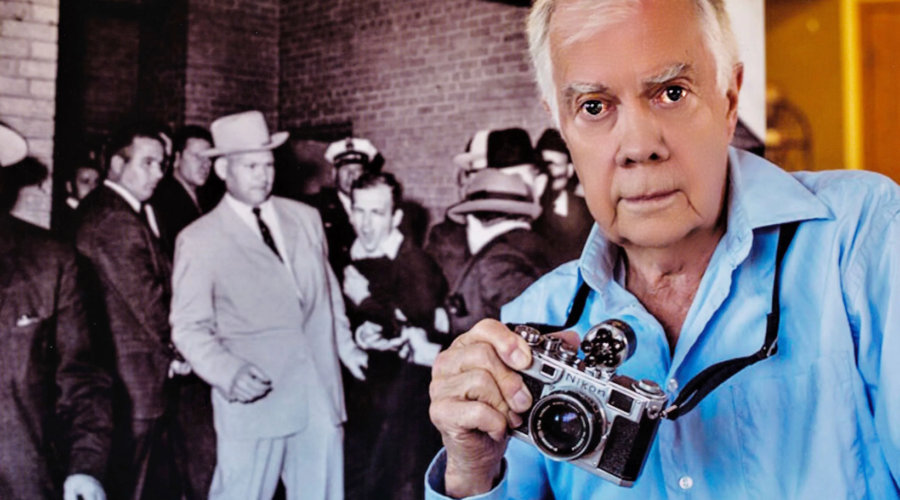

Actually it would win the Pulitzer Prize for news photography, awarded for the incomparable picture of nightclub owner Jack Ruby gunning down suspected assassin Lee Harvey Oswald as he was being transferred to the county jail. The photo showed Oswald grimacing in pain from having just been shot, smoke rings rising from his abdomen to his eyes, and the face of one of the Dallas police detectives etched in sheer terror.

But two days before that happened, on that sad Friday night, I watched as both the AP bureau and the Times Herald newsroom slowly revved up their news gathering operations, the offices cackling with the incessant popping noise from typewriters and wires service machines, as well as phones ringing almost nonstop. I made myself useful to reporters and others at the AP by fetching soft drinks, coffee and cigarettes from the machines in the lunchroom at the other end of the newspaper newsroom. I didn’t mind. It gave me an excuse for being in the middle of the newsroom overhearing reporters on the phones quizzing sources for details, as well as editors complaining that whatever copy they were getting wasn’t enough. It was understandable. This was the biggest story of everyone’s careers.

Seven years later. 1970.

I walked into the Dallas Times Herald newsroom on a Monday three days after graduating from college to become a reporter at the newspaper where I had spent the night of President Kennedy’s assassination. I was assigned a desk I remembered walking past several times while getting coffee for The Associated Press reporters in the bureau that night. Each time I passed it I remember saying to myself that this desk had my name on it. And now it really did.

The national tragedy of November 22, 1963, affected all of us in different ways. For me, it intensified my childhood dream of wanting to write and later of wanting to report the news.

In 1960, during the presidential campaign, a reporter who was roaming the country interviewing Americans of all walks of life passed through my hometown interviewing people, among them my parents in our home. His name was Jules Loh of The Associated Press New York Bureau. I spoke to him briefly, and then he made the mistake of his life. He gave me his business card. A week later I began writing him letters, one every couple of weeks or so, asking him how he had become a reporter and for advice on how to follow in those footsteps.

Jules Loh was extremely kind, and I can’t think of a instance when he didn’t reply to one of my letters. The following year he returned to my hometown to speak at a baseball banquet to which I had invited him. Later, Jules Loh was among the people who wrote letters of recommendation on my behalf for college, jobs at the Times Herald and other newspapers, graduate school, and fellowships.

And now here I was.

Almost immediately an assistant city editor gave me my first assignment. I was to attend the noon luncheon of the Dallas Council of World Affairs where a Nixon administration State Department Under Secretary was speaking about peace negotiations in Vietnam. I was soon joined at the city desk by a safari-vested photographer with a couple of cameras hanging from his neck. I recognized him immediately. It was Robert Jackson, the Times Herald photographer who had won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo of Ruby shooting Oswald.

“I’ll drive us,” he said and introduced himself. “Bob Jackson.” He was a youthful looking 36. He had been 29 when he shot the picture of Oswald’s murder.

Downstairs, I couldn’t believe the car he got into, inviting me to jump into the passenger side of his Porsche 911. For the next few minutes, as he drove us to the Fairmont Hotel, all we talked about was his Porsche, my dream car. He smiled. His pride and joy, he said, was a 1958 AC Ace Bristol, the forerunner to race car pioneer and friend Carroll Shelby’s famous Cobra.

“There were six in all of Dallas,” Jackson later loved to say, “and I had one of ‘em.”

But the moment we reached the Fairmont, his demeanor changed.

“You know what you’re supposed to do, right?” he asked.

“Call the city desk right after the speech and dictate a story,” I said.

Jackson shook his head.

“You’ll miss the next deadline,” he said. “The moment we get into the ballroom, we’ll find this Secretary of State dude. Introduce yourself. Tell him you’re 10 minutes away from deadline. Fire three questions at him and ask his aide for a copy of his prepared text. I’ll shoot some photos, then I’ve got to leave. But stick around and in 10 minutes call the city desk, ask for rewrite, and be ready to dictate from what you just got. Then go downstairs. I’m just dropping off film and coming right back to pick you up.”

It was the best journalism lesson I ever received at the Times Herald. Actually, it may have been the best advice I ever got in journalism period. The assignment editor, a hardened former Marine sergeant, had sent me off without much instruction and possibly intentionally preparing me to fail and show that I had no business working there. When I returned to the office, we exchanged glances. He looked surprised, even through the shit-eating grin on his face, that I had somehow made the afternoon’s last deadline after all.

I owed Bob Jackson. He knew how the game worked with newbies. He certainly wasn’t new, except from being newly returned to the Times Herald. He had left the paper for which he had won a Pulitzer five years after the assassination to go work at the Denver Post. Then he returned to the Times Herald just a few months before I joined the paper.

Bob was now the most famous news photographer in America for the photo that had come to be known simply as “The Shot” — and that fame had taken him some time to get used to. He had his own cross to bear in a way, and he knew what it felt like to be treated in the news business as if you didn’t belong there. He was the son of Dallas nobility, having been born into wealth and growing up in Highland Park, the poshest neighborhood in the city, attending good schools and Southern Methodist University. What made it even tougher for him was the story that he had gotten his job through one of his father’s friends, the co-publisher and editor of the Times Herald, who had reportedly lobbied the paper’s photo editor to hire Jackson.

For the record, Jackson begs to differ. During college in the 1950s, Bob became friends with Carroll Shelby who helped him combine his love of cars and photography. Ultimately, he developed a long career and history photographing car races and drivers, specializing in the annual Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, the second oldest auto race in America. Only the Indy 500 race is older. Unknown except to his friends, Jackson credits this experience for helping him land the Dallas Times Herald job.

Perhaps it is easier in Dallas newspaper circles to believe that the gods of their profession inexplicably chose to grace the Pulitzer Prize on a privileged prince of the city over all the seasoned news photographers who had snapped away in that overcrowded, poorly lit police station basement as Jack Ruby jumped out of the shadows to take justice into his own hands.

After all, a veteran Dallas Morning News photographer had shot a photo of Oswald’s murder similar to Jackson’s but depicting nowhere near the drama and emotion that Bob’s picture contains. Years later, a detailed study of all the photographers’ positions in the basement and their photographs appeared to show that Jackson — who was not placed in the most ideal location to shoot — had captured the moment and, with that, the perfect image. He had snapped “The Shot” six-tenths of a second after the photographer from the Dallas Morning News, and that split-second wait made history. Unfortunately, this only intensified some of the private bitterness and bickering that went on behind the scenes in Dallas journalism and news photography circles.

But the better photograph won the Pulitzer, proving Bob Jackson the superior photographer.

Heaven smiled on Bob Jackson even after his famous picture. The Times Herald gave him rights to the photograph, worth a small fortune. In a town and state known for its oil wealth, Bob struck the motherlode, as if he really needed one. Today he has a deal with the Fahey/Klein Gallery in Los Angeles, which charges $1,500 for individual numbered prints. He proudly notes that the No. 7 print was bought by Elton John.

Bob is now 89, living with wife Debbie in a mountain hideaway in Manitou Springs, Colo., in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. There he specializes in photographing the yearly Pikes Peak car race.

The assassination may have made him famous, but his fascination remains fast cars. In addition to the Ace, he has owned three Jaguars, five Porsches and a Lotus.

And Jackson still credits his pal Carroll Shelby with his career.

He would not have gained the experience necessary to get the job at the Dallas Times Herald that led to his Pulitzer, had it not been for their friendship.

“Regardless of what anyone says about Bob being lucky, the fact of the matter is, he deserves the credit,” Shelly Katz, former contributing photographer to Time magazine, has often told reporters. “He made the shot, period, and you can’t take it away from him.

“The proof is in the picture.”

Tony Castro, the former award winning Los Angeles columnist and author of CHICANO POWER (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is a writer-at-large with LAMonthly.org. CHICANO POWER will be republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.