How Los Angeles deals with Kevin de León and therefore with itself will show it to be either the Tinseltown viewed by its detractors — selfish and exclusive — or the city seen by its defenders: painfully troubled, but still holding on to the country’s original moral purpose and promise.

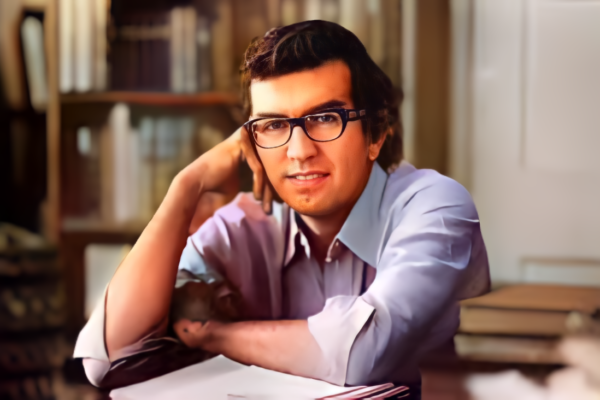

By TONY CASTRO

KEVIN DE LEÓN, WHO A YEAR AGO BECAME persona non grata from Southern California to the White House, is betting that his constituents are forgiving enough to help him re-launch his once promising political career — so damn the torpedoes. He’s running for reelection to the Los Angeles City Council where until recently he might have been mistaken for a character from The Walking Dead.

More significantly, de León is gambling that voters in his predominantly low and middle-income Latino district in their own personal way might privately agree or empathize with him on the delicate but volatile issue behind the controversial racist comments that got him and two other Latino politicians into trouble in the first place — and that maybe, on a larger scale, this secret and illegally taped recording was only the tip of the iceberg.

Amazingly, it was only a year ago that even President Joe Biden called on fellow Democrat de León to resign his council seat after a leaked tape of a political backroom full of disparaging racist comments about other minority groups embarrassingly exposed the divisive racial ethnic fissures that often still simmer in Los Angeles, the most Third World major city in America.

“When a lot of people that I called my friends and allies turned away from me, my constituents had my back,” de León said in an interview. “I understood in a deeper way the relationship that I had with my community and how that motivates and drives me. That’s why I’m still here. And that’s why I’m running.”

Call him Latino Lazarus, if he pulls this off, The Walking Dead of biblical proportions. And, if he does, don’t let the Los Angeles Times forget that earlier this year it called him a fart in print: “KDL has turned into the political version of a fart — most officials stay as far away as possible, while his fellow council members hold their nose every time they take a vote alongside him.”

Sinvergüenza would have been more like it. Someone without shame. Kevin de León might have argeed. He is, after all, the self-made poster boy for the American Dream in California or as he put it, “I am not just a defender of the California Dream. I am a product of it.” It is fitting. Kevin de León is also a product of Los Angeles’ most famous business. He believes in fantasies. Some critics say he is a fantasy of his own making, another politician tinkering with his narrative.

But he knows he blew what he had going for himself by being part of that racist-filled political conversation with two other colleagues and a labor big shot that ultimately exploded into the biggest political scandal in recent Los Angeles history.

For sure, the last year has been hell for de León, becoming a punchline and being chased out of the City Council chamber to which he had been elected in 2020 to replace the real Sinvergüenza who had bribed and scammed and collected hundreds of thousands of dollars illegally and is now about to become perhaps the only Princeton-educated Latino ever to do time in federal prison. Someone may have to remind that guy that the sign at the entrance reads “Jail,” not “Yale.”

But Kevin de León is not that guy. He’s broken no law. He is a 56-year-old Guatemalan American who was raised by a single mom in San Diego and Tijuana and strongly identifies with the Mexican culture. In his youth, he also did something quite status-climbing, Jay Gatsby-like. While attending the University of California at Santa Barbara, he began going by Kevin de León and has continued using it, though apparently never legally changing his name from Kevin Alexander Leon.

“I didn’t want to be viewed as a bastard child,” he said, not knowing his father and describing his name-change as a search for structure and roots. “De León gave me that sense that I belonged to something, to somebody — even though at the end of the day I didn’t.”

Clearly, it was a sign of upwardly mobile ambition. By adding the “de” to his surname, he was trying to give it a classier ambiance. Like Gatsby, Kevin de León “sprang from his Platonic conception of himself.” Call him The Great de León.

He was intent on being somebody. His own Daisy Buchanan? Political power.

After graduating from Pitzer College, de León was first elected to office in 2006, winning a Hollywood-Northeast LA seat in the California Assembly by defeating César Chávez’s granddaughter, of all people. He then won election to the State Senate in 2010, becoming Senate President Pro Tem and earning a reputation as an ambitious rising star in Latino politics.

But he would be dogged by controversy and scandal from almost the very start.

As an Assemblyman, he was found to have made illegal ghost votes for another Assemblymember but opposite of how that Assemblymember planned to vote. A scandal erupted, but de León avoided punishment through the forgiveness of then-Assembly Speaker Karen Bass, the future Congresswoman and mayor of Los Angeles. Some believe it cost him his chance to become the next Speaker of the Assembly. Then he foolishly ridiculed in public much of the state of California as being nothing more than “tumbleweeds.”

De León encountered more controversy during his eight years in the State Senate. He voted against a water bill when the company benefitting from his vote had previously contributed to his political campaign. Then there was persistent criticism in Sacramento over the manner in which he managed to get several bills passed.

De León carried his personal magnetism for negative publicity and scandal to the Los Angeles City Council. He raised questions over just how close he was financially to an AIDS nonprofit organization. Another time he drew condemnation attempting to stall a rapid transit project. But possibly his most embarrassing faux pas was forgetting the pledge of allegiance when asked to lead his colleagues in its recitation at the opening of a City Council meeting.

The zoom video of the incident quickly went viral, viewed with disbelief and pity hundreds of thousands of times or more throughout the country, if not the world: the ambitious and Latino upstart wanting to make a name for himself in politics who can’t remember the words of national pride that American kids learn in grade school. Play it again, please. De León starts off strong and then suddenly loses the words, stopping at the phrase “United States of America.” He pauses, mumbles “undervisible,” then quickly starts over. On the second try, de León reaches the word “America” and pauses again. He noticeably skips over part of the pledge before making his way to the finish. As soon as it was over, someone at the meeting can be heard uttering “Oof.”

When he ran for U.S. Senator and mayor of Los Angeles, he didn’t lose because of that gaffe. But it didn’t help him in inspiring non-Latino voters to vote for him or in convincing them that he was the Latino Barack Obama, someone deserving of trust and transcending the unfortunate stereotype some white voters might have of black and Latino politicians.

If he was your kid, or you knew him personally, you would have to feel for him. Remember that line about him not wanting “to be viewed as a bastard child”? Growing up, de León was torn not knowing who his father was, as well as being acutely aware that he was an out of wedlock child, the son of a mother and father who had their own separate families. He wanted a father, but he came to understand that “I am who I am today because of my mother.”

“I don’t go though my life any longer wishing I had a father,” he said in an interview. “I believe I have surpassed that moment in realizing that I am a product of my mother.”

But he felt a resentment that drove him — “a chip on my shoulder… I wasn’t good enough, maybe.”

The veteran political journalist Dan Walters, who has witnessed it all in California and in America, saw in de León “an archetypal up-from-poverty political striver” with an unquenched need for validation and an obvious cry for attention such as when he threw a lavish “inauguration” ceremony in Sacramento after winning the Senate President Pro Tem position. Some are still laughing about it at the state capitol.

“California is the greatest beacon of opportunity the world has ever known,” de León has said in his defense. “But we didn’t get here through years of political seniority — we built it through acts of audacity.”

So Is there enough audacity in that uber-ambition to get reelected to the city Council in 2024 when his name and reputation have been further tarnished and poisoned by enemies and former friends alike over the past year?

In next spring’s primary, de León will face at least two other similarly ambitious former colleagues from the State Legislature, who are using the audio taped racist-scandal to maintain that Los Angeles needs new blood in order to heal the wounds that the Eastside councilman and two other fellow Latino City Council members created by their language in the leaked audio tape.

One of those other two council members heard on the tape, the then City Council President Nury Martinez, resigned. The third councilmember, Gil Cedillo, had already lost his reelection bid in the primary earlier in the year.

But are Angelenos — be they Black, white, Latino, Asian, Jewish, Muslim or any other group — so naïve as to believe that Latinos and African-Americans in particular live in perfect racial ethnic harmony in this modern world and culture? If they do, in what fairy tale Hallmark card have they been living in?

Since the scandal erupted, the charismatic de León has focused his attention almost exclusively on his Eastside district, doubling down on his constituents’ needs and neighborhood issues — and reestablishing his community political organizational ties — which were the backbone of his initial success into the world of California’s often misunderstood and maligned Latino politics. His own politics became even more liberal than that of most Latino politicians, though it did endear him to progressives in the state whose backing helped him make a respectable showing when he challenged Senator Dianne Feinstein in 2018.

A special note in that campaign was one of De León’s political ads titled “Our Time” that clearly underscored the vision that drives him politically. The ad attacked Feinstein and then President Donald Trump for bashing immigrants and had a scene of a single mother, a housekeeper like De León’s late mom Carmen, being hauled away by immigration agents. “This is our story,” de León says in the ad. “It’s time to stand up and fight back.”

Then and today in his every day political life today, de León speaks about and to Latinos with an urgency that understandably inspires and moves both Latino Americans and immigrants, especially those in single mother families. And make no mistake, it is a message not intended for all, but certainly for the people who are the heart and soul of his district’s constituency, which is likely where de León will win or lose his upcoming reelection. That district takes in all or portions of downtown, Boyle Heights and El Sereno on the Eastside and Eagle Rock in the Northeast.

“He really helped the Latino community in and around his district, and they will never forget that ” said Maria Costa, a Los Angeles pollster who focuses on Latino communities. “Honestly, he still has a lot of support there, and he has spent the summer going out and about trying to repair his reputation. And his staff has being using the usual playbook for political rehabilitation, right down to ‘getting your picture taken eating food at a local restaurant.’”

Is de León counting on the phenomenon that too often voters have surprisingly short memories and that politicians’ followers and political supporters don’t care what kind of scandal their leaders get themselves into, so long as they deliver on what’s important to their political base?

Early proof of that may have been that a campaign to recall de León earlier this year failed miserably when its leaders couldn’t muster enough signatures to get the issue on the ballot — this in California, the state that’s the easiest to get a respectable ballot measure before the voters, and at a time when professional signature-gathering organizations can virtually guarantee doing just that.

Even a Los Angeles Times poll of voters in his district also indicated that de León may not be as vulnerable as some had believed. Only 51% of the voters in his district thought he should resign, and an even lower 43% of Latinos felt the same way. And that was a poll taken last January when the racist comments scandal was still fresh and in the news and the anti-de León protests in the council chambers so intense that he was staying away.

Who would’ve thought at that time that the embattled Kevin de León had a comeback path? And could that snarky Los Angeles Times rhetorical remark after the botched recall attempt prove to be prophetic?

“Did those predicting the death of de León’s political career miss something?”

Give him credit. De León is a born campaigner. He had plans to go places, and he had goals. But he was termed out of office in the legislature, which is why he ran for the City Council where long futures are often bleak in politics, unless you have designs on running for mayor. But still, no Los Angeles mayor has ever successfully moved on to any higher office in modern times. De León insists his goal in L.A. was just to serve and help improve the lives of his constituents.

So when de León and those other two former council members met with the head of the politically influential County Federation of Labor, their intention was far from committing political suicide. Their goal had been to strategize as Los Angeles’ presumed Latino leadership on how to take on the City Council’s once-a-decade redistricting process — and to prevent it from again short-changing Latino representation by carving out districts more favorable to the city’s old-guard politicians as well as to other non-Latino constituencies.

From experience, de León and those other two former councilmembers were intimately aware of how redistricting battles in Los Angeles underscore the way big city leaders — often Democrats — have historically used gerrymandering for their political advantage, much the way Republican lawmakers have redrawn legislative lines to secure or expand their control over some statehouses.

There is no denying the disproportionate and gross City Council underrepresentation of Latinos who comprise almost half of Los Angeles’ 3.8 million people but hold only a third of the 15 City Council seats. At the time of that controversial meeting, there were only four Latinos on the City Council. In comparison, Blacks represent 8% of the population but hold three seats — 20% of the City Council. Today, there are five Latino members of the City Council, still only a third of the lawmaking body.

This may explain why In the leaked audio tape of that meeting, de León can be heard comparing African-American representation on the City Council to the “The Wizard of Oz” — projecting a presence that is much larger than their actual numbers.

It is noteworthy that de León has expressed remorse for not rebuking former City Council President Nury Martinez and others, including the former head of the county’s Federation of Labor, for their racist statements secretly recorded at the labor organization’s headquarters and then apparently leaked by someone from that office.

The Los Angeles Police Department is currently investigating the leaked recording, which was illegal under California law, with suspicion focused on a disgruntled employee of the Federation of Labor, according to Los Angeles Magazine.

Additionally, de León has apologized for agreeing with Martinez in calling the Black adopted son of a fellow Council member a prop, adding the child’s presence at a political event was “just like when Nury brings her yard bag or the Louis Vuitton bag.” He later called his comment “a flippant remark.”

But he stands firmly behind his “Wizard of Oz” comment.

“The context of our conversation was about redistricting and ensuring equal representation,” de León has said. “You have to look no further than the maps that were drawn. Are they fully reflective of the demographics of the city? Not really.”

And today, the redistricting of the City Council districts remains unsettled. An effort to create a fair and equitable redistricting map by representatives of each councilmember dragged on for the better part of two years. Ultimately, it was rejected for a substitute redistricting map that was virtually the same one created a decade earlier with all its built-in biases and flaws that have failed to curb the political corruption that has led to a handful of councilmembers going to prison, or in route to prison at the moment.

Now it would appear that city officials are preparing to put the question to voters next year as to how to proceed, possibly with an option to enlarge the City Council by as many as 10 members.

But don’t hold your breath. For as Sara Sadhwani — an assistant politics professor at Pomona College who was part of the academic panel that suggested some of the City Council redistricting reforms about power, who holds it, and are they really interested in sharing it — has said:

“It’s a rare thing to see a councilmember or any legislator that has such a power have a willingness to relinquish it.”

That, too, could be said of Kevin de León who in 2020 succeeded City Councilmember Jose Huizar, who was enmeshed in a massive corruption scandal that led to his indictment and conviction. He is now awaiting sentencing on federal racketeering and tax evasion charges.

In 2020 de León won election outright in the primary with 52% of the vote. If no one receives a majority of the vote in the primary next March, the top two vote-getters will face off in November.

Is there any doubt that the reelection campaign will be messy, dirty and a bizarre spectacle at times? This is post-Trumpean America, after all, where politics has become a free-for-all entertainment sport.

But that election will also be more than a referendum on Kevin de León. It will be a referendum on Los Angeles. The way Angelenos, particularly in his district, react to de León and his plea for forgiveness and a second chance will define for years what kind of community it really is. How Los Angeles deals with de León, and therefore with itself will show it to be either the Tinseltown seen by its detractors — selfish and exclusive — or the city seen by its defenders: painfully troubled, but still holding on to the country’s original moral purpose and promise. It may be Kevin de Leon’s role not only to struggle for his rightful share of his American Dream, but also to recall the rest of Los Angeles to its own sense of conscience and destiny.

Tony Castro, the former award winning Los Angeles columnist and author of CHICANO POWER (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is a writer-at-large with LAMonthly.org. CHICANO POWER will be republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.

CHICANO POWER 50 Years Reflections is a series of stories examining the Latino civil rights history of the more than five decades since the advent of the Chicano Movement in Southern California and the LA County Sheriff’s deputy shooting death of Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar whose reporting on inequities and discrimination against Latinos underscored those social, economic and political injustices.

Journalist and author Tony Castro, who in 1978 succeeded Salazar as the leading Chicano voice in a city of almost four million of which more than half are Latino, ruminates about the Chicano Movement today and about Latinos in faithful pursuit of the American Dream: their progress amid broken promises and ongoing challenges faced by Latinos in politics and in all aspects of life — and in particular about the special difficulties of Latino columnists following in Salazar’s footsteps.

In these stories of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Castro invites readers into the world of Latinos, his world, chronicling the experiences about race, culture, identity, and belonging that have shaped those who led the movement, as well as himself. As much as this story is about adversity, it is also about tremendous resilience. And Castro pulls back the curtain and opens up about his career and personal life — and his struggles balancing himself in a society discriminating against so many like him, and his journey toward open heartedness.

Castro, a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, was an award–winning columnist for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, writing in the southwest, and in central America in the late 1970s and 1980s. He later covered politics and civil rights for the Los Angeles Daily News.