By Ashley Chase

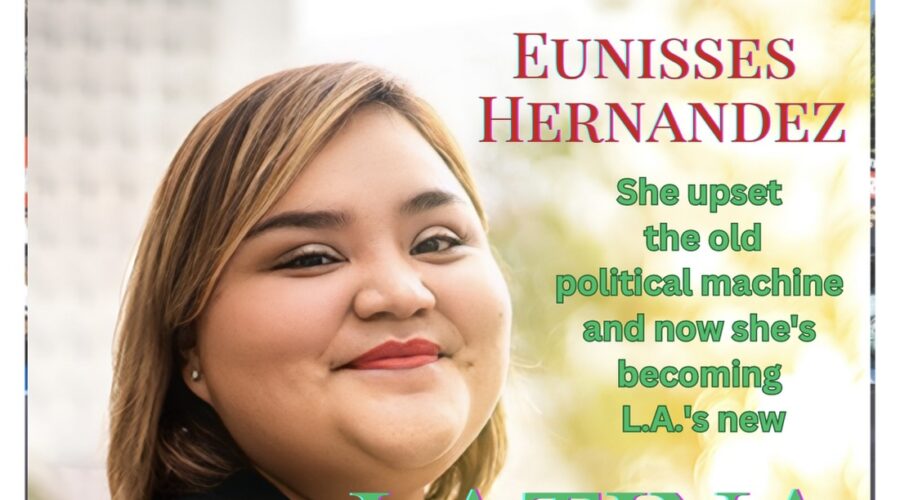

EVEN BEFORE SHE UPSET THE LATINO political establishment to win a seat on the Los Angeles City Council, Eunisses Hernandez had dedicated her public career not to be a politician forever but to develop the next group of future leaders — something few, if any, local Latino leaders have ever done.

“Part of my job is to build the bench of the next people,” Hernandez said not long after unseating incumbent Gil Cedillo in the June 2022 primary to eventually represent Council District 1, including the northeast side of the city.

“People who understand that we need to dig in our heels and put people over profit, people over politics. And [people] who understand the ways in which you can build community power so that you don’t need to rely on special interest groups or dirty money to get you into those seats.”

Last week Hernandez celebrated seeing that one of the keystones to that promise — the 2020 county voter-approved landmark criminal justice reform known as Measure J — had been upheld by the California Court of Appeal.

Passed near the close of tumultuous 2020 following the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Measure J was a telling message that voters wanted more of their tax money directed to mental health care, economic opportunity and other public safety alternatives to police, prosecution and jail.

“Now that it’s permanent, we need all the money,” said overjoyed Hernandez, who co-chaired the Re-Imagine L.A. County campaign supporting Measure J. “We’ve only gotten a fraction of what Measure J is supposed to be giving to the community. It’s supposed to be close to a billion dollars.”

Measure J requires that 10% of locally generated, unrestricted county money — estimated between $360 million and $900 million — be spent on a variety of social services, including housing, mental health treatment and investments in communities disproportionally harmed by racism. The county will be prohibited from using the money on prisons, jails or law enforcement agencies.

The amount of the Measure J 10% set-aside in the county’s 2023-24 budget is $288.3 million, along with a $198 million rollover from the previous year, bringing the available amount to $486 million. The funding is available for social services, including housing, mental health treatment and alternatives to incarceration.

And all that scares the bejesus out of conservatives, but especially law-enforcement groups who say that the money will inevitably be slashed from law enforcement. It was the Coalition of County Unions, which includes the Association of Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, that filed a lawsuit against the county trying to stop Measure J.

In June 2021, a judge ruled in favor of the unions to overturn the measure, citing the measure limited how the Board of Supervisors could decide revenue allocations.

The recent court of appeal ruling found the state’s constitution allows counties to implement budget strategies into their charters.

Community groups are celebrating a court ruling upholding Measure J.

The Re-Imagine LA Coalition, including more than 100 organizations, is urging county supervisors to fully fund Measure J and enact a “care first budget.”

In the years Measure J remained in legal proceedings, the Board of Supervisors moved forward to create the Care First Community Investment fund and allocated approximately $400 million to Measure J related programs and services.

Janice Hahn, chair of the Board of Supervisors, said in a statement that “the voters of L.A. County made it clear they want us to spend more money keeping people out of jail, and this appeals court has upheld their wishes.”

Hernandez can’t wait for Measure J to be implemented. Could she be the West Coast version of AOC, Los Angeles’ own version of Latina powerhouse Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the irrepressible New York congresswoman who is both politician and activist and continues to upset the status quo and the so-called powers that be?

“For far too long the needs of our Black and brown communities fell on the budget chopping block and as a result these communities have paid the price,” she says. “Measure J will now change that.”

For Hernandez, this has been an especially satisfactory triumph that has been years in the making.

In 2020, she co-founded La Defensa, a women-led organization supporting the reduction of incarcerated people in Los Angeles County. It was the same year she co-chaired Measure J, campaigning for community reinvestment and incarceration alternatives. She also co-chaired the ballot initiative campaign with future Assemblymember Isaac Bryan and future councilmember Hugo Soto-Martinez. The ballot initiative passed with 57.12% of the vote.

A self-described police and prison abolitionist, Hernandez then entered the 2022 City Council primary endorsed by progressive groups and leaders such as City Councilman Mike Bonin, legendary, farm labor activist Dolores Huerta, and the Los Angeles Times.

Soon after her election, Hernandez began drawing comparisons to Gloria Molina, the former legislator, councilwoman, and county supervisor, who in 1982 took on the powerful Eastside Latino political machine of the legendary Richard Alatorre — and beat it, winning election as the first Latina to the California State Assembly.

Molina became one of Hernandez’s role models.

“She blazed the trail for women — and especially for Latinas — in local government and we owe her a debt of gratitude for her decades of service to our city and our county,” Hernandez said

earlier this year, upon hearing the news of Molina’s terminal illness. “I join all Angelenos in offering her my prayers and support during this time.

“We stand on the shoulders of the giants who came before us, and Supervisor Molina is one of a kind.”

It was not just in defeating the incumbent Gil Cedillo, that quickly put Hernandez under the spotlight as someone walking in Molina’s footsteps.

Soon came to scandal of all scandals that is undermined Latino politics in Los Angeles. Three Los Angeles City Council members were secretly recorded, making insensitive, racist remarks about African American politicians and some of their children.

Then City Council President Nury Martinez was forced to resign. Councilman Cedillo was already a lame duck, and would soon leave the council. Councilman Kevin de Leon refused to resign, even though those calling for his resignation included president, Joe Biden. What arrogance, right? But he soon became a pariah in his district and in the council.

“It’s a different place to be in when the people who have these values and views, anti-Blackness and racism and homophobia, are the ones in leadership that look like us,” said Hernandez. “This type of racism and anti-Blackness and homophobia is covered by faces that have been adored and loved by community, and that people have looked up to.

“I felt that they took us back several decades.”

But it also cleared the air of the stench of scandal. By the time Hernandez joined the council last December, former Eastside councilman José Huizar had also left in disgrace. Today the City Council has been virtually cleared of the old, political powers. The only exception is Monica Rodriguez, who was elected in 2017 to represent part of the San Fernando Valley no part of the traditional Los Angeles stomping ground controlled by the old Latino political establishment.

Hernandez understands what that transition means. Those political powers of the past were once well- intentioned leaders who had their own strong points but perhaps stayed around too long, much like Gil Cedillo, the councilman she defeated and replaced.

“The frustrating part is that I appreciate the work he’s done” Hernandez said in an interview with the Boulevard Sentinel, “since I know that he has paved the way for people like me and others to run.

“But at some point, we have to recognize that these people are no longer the people they were 10 or 15 years ago — and that is very problematic.”