DACA Immigrants Can Become Cops

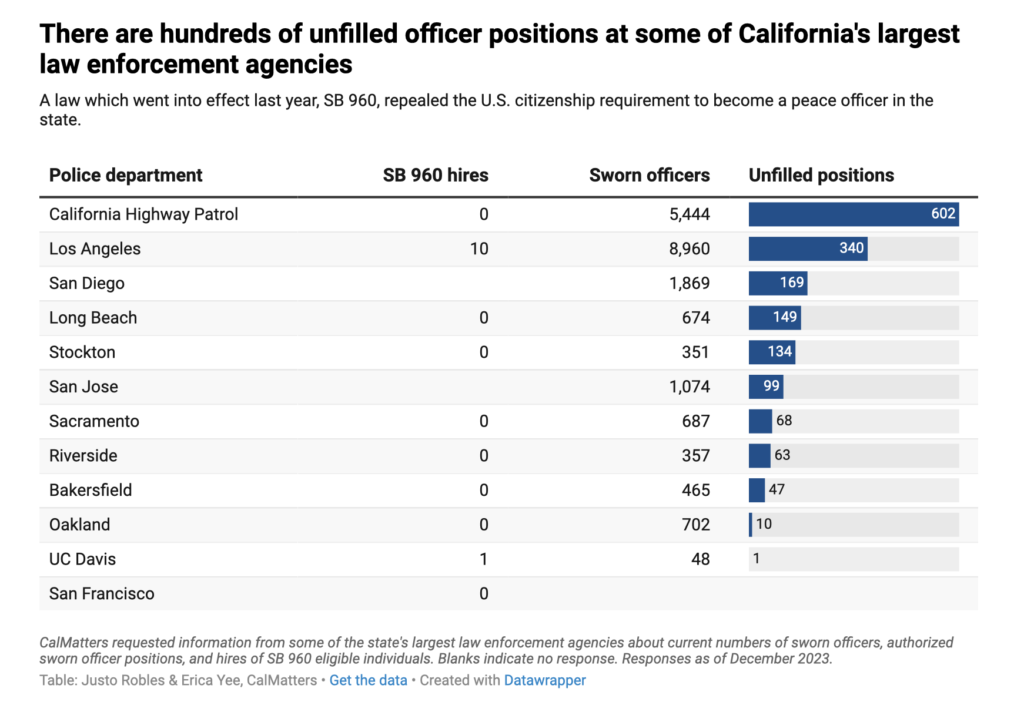

Many law enforcement departments are having trouble filling vacancies, but they’re slow to use a state law that lets them hire immigrants legally under the federal DACA program. Only the LAPD and the UC Davis police have given it a chance.

By JUSTO ROBLES, Cal Matters

Dressed in a pristine dark blue uniform, 10 new officers raised their right hands and swore to defend the constitution of a state they weren’t born in but that they have called home for two decades or longer.

They are the first officers hired by the Los Angeles Police Department under a 1-year-old California law that repealed the U.S. citizenship requirement to become a peace officer in the state.

Before the law took effect, California, like most states, had required its peace officers to be U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents who have applied for citizenship.

The state law, SB 960, makes applicants with federal work authorization eligible to become officers.

According to supporters, the new law would make an effective recruiting tool at a time of persistent patrol officer shortages and declining staff levels. They said if immigrants were encouraged to apply, law enforcement agencies could gain more diverse, multilingual officers.

It is only recently that the LAPD announced a policy memorializing the right of DACA recipients to be employed as officers.

DACA is the federal program known as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which since 2012 has protected from deportation more than half a million undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.

Those first 10 DACA recipients are part of a force of 8,960 sworn officers. The LAPD Is funded for 9,300 positions, according to officials.

“Los Angeles Police Department officers who are in the U.S. pursuant to DACA have the authority to possess a firearm for use in the performance of their official duties or other law enforcement purposes,” said Lizabeth Rhodes, senior legal and policy advisor to the chief of police, during a December Los Angeles Police Commission meeting.

Rhodes added that while the federal Gun Control Act of 1968 established that “illegal aliens” were forbidden to possess firearms, the law contained exceptions, including cases where the firearm or ammunition is issued by a state or department.

Capt. Robin Petillo, in LAPD’s recruitment and employment division, confirmed that the newly minted officers who are DACA recipients will possess department-issued firearms on and off duty.

LAPD Chief Michel Moore says his department is taking the nationwide lead on the unique immigration challenge: allowing non-citizen DACA recipients who become sworn officers the ability to carry a firearm full-time.

“We’ve sought information from our federal and state and City attorney to understand what does the policy nced to discuss to articulate the basis of which a DACA individual, now a police officer, can lawfully carry and possess a firearm and ammunition,” said Moore.

In December the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners “unanimously approved” the outline of a policy that would allow DACA recipients the capacity to carry a firearm off the job.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League, which represents over 9,200 officers, is backing the proposed policy.

“It has been the long-standing position of the Los Angeles Police Protective League that our members are police officers 24-hours per day and as such they should be afforded all the legal rights and protections the same if they were clocked into their respective shifts,” the League wrote in a statement.

Federal and state law allow for DACA individuals who are not US residents or citizens to possess firearms, as long as it’s within the course and scope of their law enforcement work, officials explained.

Sen. Nancy Skinner, the Democrat from Oakland who sponsored the law under SB 960, called the citizenship rule archaic in a statement and said the new law could “improve the current relationship between law enforcement and communities of color by increasing the visibility and representation of people from the neighborhood.”

But an informal CalMatters poll of the largest local and state police departments in California suggests many have been slow to hire the newly eligible immigrants. Only those 10 in Los Angeles and another in the UC Davis Police Department appear to be the only law officers so far to have gotten jobs through the law, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2023.

“Our police officers are facing a workforce shortage, as other professions are,” Skinner said. “We need to have people that want to serve in these public safety roles. So we want to eliminate any unreasonable barriers for people from being able to serve.”

California cities are struggling to hire enough officers, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Public Policy Institute of California this month reported the number of patrol officers per 100,000 people is at its lowest point since at least 1991. Though the steepest declines occurred during the Great Recession from 2007 and 2009, staffing levels still have not recovered.

In 2022 alone, the state commission that certifies newly trained officers issued 2,424 basic certifications, down 53% from 2020 when it awarded 4,530 certifications.

Though the Golden State is home to the country’s largest immigrant population, for years it barred them from many careers because professional licenses required Social Security numbers.

Then new laws took effect in 2014 allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain professional licenses. Today they can be lawyers, doctors, nurses and other licensed professionals.

It took nearly a decade longer for California to join states like Colorado and Illinois, which allow DACA beneficiaries to put on a badge.

“I found it highly ironic that you can be a U.S. military police officer without being a U.S. citizen. So you can serve in our armed forces and, in effect, be the law enforcement for our armed forces,” Skinner said. “And yet, California had a rule that you could not be a police officer.”

Though most state legislators ultimately approved the bill, there was early opposition. At an Assembly Public Safety hearing in June 2022, Skinner introduced UC Davis Police Chief Joe Farrow and UC Davis graduate Ernesto Moron to testify for the bill. Moron ultimately became a police officer in the UC Davis, Moron ultimately became an officer in the UC Davis Police Department.

“During my senior year I attended the UC Davis Police Academy and I distinguished myself in several disciplines,” Moron said as he sat next to Farrow. “Typically top candidates from the academy are evaluated for sworn police positions, and I believe UC Davis (police department) had every intention to hire me, but current law prohibits it.

“I passed the same police background check that sworn officers must pass to get the position I am today. This bill will allow me and countless others the opportunity to fulfill my dream of serving the communities where I was raised.”

Skinner stressed at the hearing that the bill would not allow undocumented immigrants who lack work authorization to be hired as peace officers.

Nevertheless several lawmakers opposed the bill, including Assemblymember Tom Lackey, a Republican from Palmdale and a former California Highway Patrol background investigator.

“California law enforcement agencies have limited capabilities to determine the criminal background of foreign nationals, which the federal government does prior to granting citizenship that enables service as a peace officer in most agencies,” Lackey told CalMatters in a statement.

“Additionally, someone who is not legally in the U.S. cannot legally possess a firearm, which is an essential tool for officers,” he said.

The Sacramento Police Department, which had more than 60 sworn officer positions to fill as of December 2023, said it hasn’t hired anyone under the new law, in part because of firearm safety concerns.

“There have been background issues and additional legal hoops that prevented them from being hired as peace officers. For example, there is a requirement to be a citizen to possess a firearm,” the Sacramento Police Department said in a statement.

“Additionally, someone who is not legally in the U.S. cannot legally possess a firearm, which is an essential tool for officers,” he said.

The Sacramento Police Department, which had more than 60 sworn officer positions to fill as of December 2023, said it hasn’t hired anyone under the new law, in part because of firearm safety concerns.

“There have been background issues and additional legal hoops that prevented them from being hired as peace officers. For example, there is a requirement to be a citizen to possess a firearm,” the Sacramento Police Department said in a statement.

Farrow, at UC Davis, said he was not surprised that there is opposition from critics who raised concerns about vetting noncitizens.

“People associate it with what they see on TV,” Farrow said. “They associate this crowded border and people climbing over the wall to get into this country and the next day we hire them as a police officer. We would never do that.

“You don’t have to show proof of citizenship — that’s it. If you have a legal work permit by the federal government, then you’re subject to a complete background check,” he said, “the same as I went through to become a police officer.”

n order to receive DACA status, petitioners must have been under the age of 31 as of June 2012 and have arrived in the U.S. before reaching their 16th birthday. They also must lack any serious criminal records.

Though DACA recipients receive work authorization, they don’t have a path to permanent legal status or citizenship. Moron and hundreds of thousands of other DACA enrollees must renew their DACA status every two years.

But the program is enmeshed in a years-long legal battle over its future.

Last year, at the request of Republican led states, a federal judge in Texas declared the DACA immigration program unlawful. While the judge didn’t order the termination of DACA, the program cannot receive new applicants.

And if a DACA recipient loses their protected status, they’d likely lose eligibility to work as a police officer, said Marc Reina, an LAPD deputy chief, at a December police commission meeting.

Farrow said he decided to hire and get Moron trained as an officer because of his character and competency.

“Competency is your training, your education, your background —military, non-military — your school,” Farrow said. “The character is who you are — are you honest, are you giving? I can train the competency but can’t train the character.”

Moron’s long-sought dream finally materialized when Farrow handed him a badge at that small swearing-in ceremony at the UC Davis police department. The kid who was told to be afraid of police because he could get deported gained the authority to protect the communities that took him in as a young immigrant.

“I’ve been here for 21 years, and I always wanted to help my community,” Moron said. “I think everyone should have a shot at something they want to do. I’ve been waiting for this for a while.”

Justo Robles was born and raised in Lima, Peru. He is a graduate of Rutgers University, and his work has appeared in work has appeared in The Guardian, NBC News, and CBS News. He can be contacted at kervy@calmatters.org

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. Published with permission of CalMatters

Photo 1

Ernesto Moron.jpg

caption

UC Davis Police officer Ernesto Moron repeats the oath as it is read to him by Chief Joe Farrow at his swearing-in ceremony at the UC Davis Police department.

Photos by Fred Greaves for CalMatters