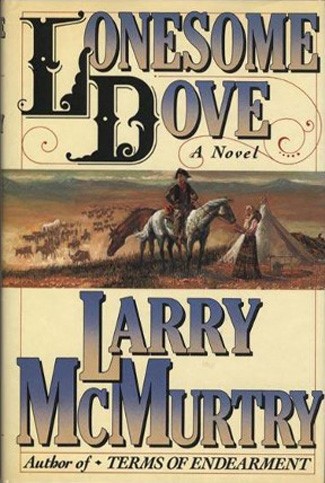

‘Terms of Endearment’ followed ‘The Last Picture Show’ with great fanfare, but it was his Pulitzer Prize-winning ‘Lonesome Dove’ that cemented his legacy as one of America’s best writers

The list of Texans that have spent their writing lives chronicling their roots is rather long and impressive, and includes names like Dobie, Webb and Graves.

For many years, J. Frank Dobie was considered the preeminent voice of Texas and Southwestern culture. Walter Prescott Webb was the esteemed historian whose books put the American West in a broader national and international perspective.

John Graves evoked the spirit of the land and its people and capped his career with his beautiful elegy to the meandering Brazos in Goodbye to a River. Few American writers have fully captured the depiction of small-town life like the late playwright Horton Foote.

Katherine Anne Porter, William Humphrey, Billy Lee Brammer and Terry Southern were among other native sons and daughters who made their own indelible marks on the literary landscape.

However, considering a half-century of writing that featured an impressive body of work (more than 40 books), including a Pulitzer Prize and countless other literary awards, Larry McMurtry surely emerged as the Lone Star state’s consummate writer of record. His landmark novel Lonesome Dove was published in 1985 and was honored with the Pulitzer the following year.

He is the son and grandson of West Texas cattlemen who was raised in what he once termed a “bookless” region. McMurtry said he could not recall even the presence of a traditional family bible, which was commonly found in most homes of that era.

As a boy, he remembered listening intently to his uncles’ storytelling on the front porch of the family home. That oral tradition represented the way most family and regional history had been passed along to future generations.

He had the good fortune as a young boy of receiving a box filled with nineteen books from an older cousin who had been deployed in World War ll. He considered this gift to be the true beginning of his education that would ultimately lead him into a life of reading, writing and book collecting.

McMurtry’s life as a writer began in the early 1960s with his novel Horseman, Pass By, and made famous by its conversion into the movie Hud. His book The Last Picture Show was published in 1966, and the subsequent movie scored another hit at the box office and now holds classic status with many critics.

Terms of Endearment followed with great fanfare, but it was Lonesome Dove that cemented his legacy as one of America’s best writers.

While having gained his reputation as a western writer, McMurtry has always shown artful skill in navigating contemporary themes and has been lauded by critics as one of the few male writers who could comfortably and accurately write women’s characters.

McMurtry tired of fiction at some point in his career and began writing about his own life, while focusing on time, place and literature — and his relationship to each.

Even in his early books set in the Old West, McMurtry attempted to destroy the notion of the good guys wearing white hats and the bad guys black hats. In his stories, good and evil always walked a thin tightrope in tandem, and occasionally switched hats in the process.

He infused his novels with prostitutes, thieves, Comanche warriors, and often portrayed them as sympathetic figures. His books recorded the gradual confinement of the drifting cowboy, as roads, fences and farms began to carve up and divide the open plain.

McMurtry spent much of his life debunking the romanticism of the West and the entire cowboy myth, while still inadvertently enhancing that legacy. He painted a rather grim picture of the difficult and lonely lifestyle the cowboy lived. He tried to demystify his subjects with irony and parody. And yet many of his readers have clung to their own romantic notions of the cowboy lifestyle.

He created two of the greatest characters in recent contemporary literature with the introduction of the two former Texas Rangers in Lonesome Dove — the pragmatic Captain Woodrow Call and the whimsical and philosophical Augustus McCrae.

McMurtry always represented the single biggest influence of my reading and writing life and was the force that underscored and strengthened my Texas roots, even though I left the state more than four decades ago.

His ability to weave history, folklore and the philosophy of a region into his storytelling helped me connect (and reconnect) with the place I was born and raised. He taught me the strengths and the weaknesses of my home state and has always made me appreciate the best it had to offer—and also acknowledge some of its less-than-flattering qualities.

After seeing the movie Hud, and then reading The Last Picture Show during my college years, I made a veritable dash to my local bookstore to discover his earlier work such as In a Narrow Grave, which introduced many of the central themes he would eventually develop in later books.

While living in my first post-college apartment in the Rice University area of Houston, I was devouring anything McMurtry wrote, and discovered several decades later that he and his young son James had been living right around the corner from me. He was then a young English professor at Rice and was always rather conspicuous on campus by wearing a tee-shirt that read “Minor Regional Novelist.”

I never met Larry McMurtry, even though I eventually entered the book publishing field and worked with hundreds of authors during my career. I was always secretly a bit envious that Simon & Schuster had been the publisher of most of his work — and not the company I worked for, Houghton Mifflin.

After reading a number of his books, I found myself preparing a few remarks that I might use in tribute if ever having the occasion of meeting him face-to-face. I will even admit to rehearsing my lines.

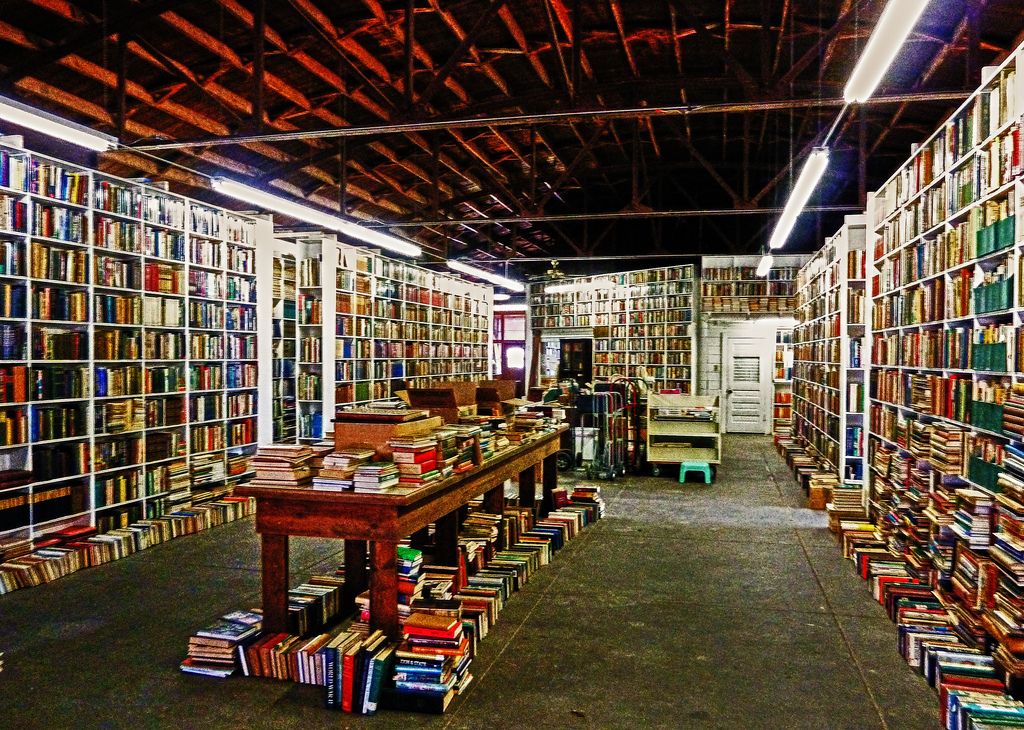

That opportunity finally arrived on a business trip to Tucson where he was appearing at the venerable Book Mark. More than 200 people packed the old barn-like space for the evening event. The bookstore staff members there knew of my great loyalty to his work and had arranged a meeting with him after the affair concluded.

However, I noticed that his presentation that night was completely listless and uninspired, and quickly realized that he was still suffering from a depression that had lingered after a recent heart attack and by-pass surgery.

Many years later after reading one of his memoirs, I began to understand the dramatic and profound impact the surgery had made on McMurtry’s life. I later learned that it had taken him several years to regain his voracious appetite for reading. He acknowledged having gone through the motions as a writer and had felt a great distance from the words that he typed on the page in front of him.

That evening during the Book Mark event, he astonished his fans by quoting William Faulkner, who had once said that there comes a time for many writers to “break the pencil and just walk away.”

I informed the surprised young publicist that I wouldn’t need that meeting with him after all. I decided to keep that undelivered tribute to myself, and then watched from the back of the room as the crowd of excited attendees lined up at his autograph table to deliver their own tributes. The scene there reminded me that he had heard the gushing praise of his fans for years and had listened to just about all the personal testimonials imaginable. He didn’t need mine. It sounded very much like all the others that night.

McMurtry always professed to be a reader first, and a writer second, as his love of the written word and admiration for great books was exemplified in his various memoirs and later works. His extraordinary home library of more than 20,000 volumes was testament in itself of his ongoing reading quest.

Thankfully, for his vast loyal readership, he chose not to “break the pencil” after that health scare and continued his writing life. He subsequently published many more works of quality and consequence in intervening years.

McMurtry lived part of each year in his hometown of Archer City, a few miles south of Wichita Falls in northwest Texas, and assembled one of the great collections of used, out-of-print and rare books in the country at his Booked Up stores. Those stores once encompassed a good portion of the downtown area and were located just down the street from the theater featured in the movie, The Last Picture Show.

At one time, he had collected more than 450,000 volumes in various buildings he had purchased in the town center. He held an auction to pare down his stock and effectively reduce his inventory by almost three-fourths to make it more manageable.

I have read that he was known to spend considerable time at the local Dairy Queen while doing his reading. In fact, he claimed that it was about the only spot in town to eat.

I had often envisioned the idea of making a trip from my Southern California home to Archer City and visiting the book town that he created.

I must admit that it might have been tempting to stop by the Dairy Queen and press my face against the glass window to see if I could glimpse a solitary figure at a table immersed in his book.

However, before ever taking that trip to Archer City, I took a solid vow to restrain myself from slipping into the booth across from him and betraying that promise I had made to myself many years earlier.

Instead, I decided to simply send best wishes to my favorite author as I drove past the city limits sign on my way out of town.

Bob Vickrey is a former publisher’s representative for Houghton Mifflin. After retiring from book publishing in 2008, he resurrected his writing career that had begun years earlier while studying journalism at Baylor University.