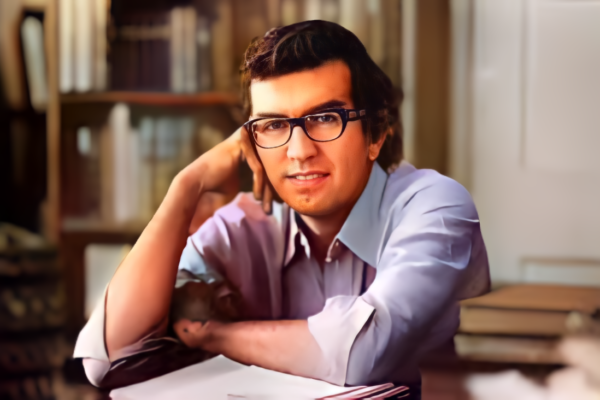

J.D had that rare gift of capturing heartbreak and hope all in one breath. He could take a moment, a feeling, and turn it into something timeless. It wasn’t just music; it was emotion set to melody. And like all great songwriters, he wrote from a place of truth.

When I met J.D. Souther, I was fresh to Los Angeles, wide-eyed and ready to take on the world—or at least the corner of it that was the Los Angeles Herald Examiner in 1978. I had just landed a gig writing a column for them and was trying to get my bearings in this new, sun-drenched city where the palm trees sway, the smog hangs like a veil of mystery, and stars seem to fall from the sky into the nearest bar.

My evenings were spent at Lucy’s El Adobe Café in Hollywood. I didn’t go there because I knew it was a celebrity haunt—back then, I barely knew what Lucy’s was, let alone who frequented it. No, I went because Frank Casado, the owner’s husband, practically dragged me in every night. Frank was a gruff man with a heart of gold, calling me “kid” as though he had christened me anew. I was 30 at the time, but I guess my 120-pound frame and perpetual sense of wide-eyed bewilderment made me look younger.

On my third or fourth night at Lucy’s, Frank introduced me to someone, giving me my now-infamous nickname: “This is the new kid in town.” I nearly choked on my margarita. The New Kid in Town was, of course, one of the biggest hits by the Eagles. I stammered, protested—no, I was just a columnist, not a rock star—and Frank shrugged it off.

“No problem,” he said with a grin. “The guy who wrote that song is here all the time.”

Right on cue, Frank spotted JD Souther, sitting alone at a table, looking like he was waiting for someone or something. Frank marched me over and made the awkward introduction: “This here’s J.D. Souther, and this is the new kid in town.”

Souther smiled, his eyes twinkling with amusement, and I found myself apologizing. “I don’t call myself that,” I said. “Frank’s just, well… Frank.”

J.D. leaned back, and with a bemused grin, he said, “Hey, the title probably fits you as well as it does anybody else.” We laughed, and the ice broke.

I didn’t know much about Souther then. In my world of bylines and deadlines, I had only a passing knowledge of the musicians who were defining the California sound. But what struck me instantly about J.D. was how normal he was—or at least as normal as a guy who could write songs that defined an entire era could be. He had this calm, Detroit-meets-Hollywood vibe, a laid-back cool that wasn’t forced, just there. He was like that classic T-shirt you pull on without thinking—it just feels right.

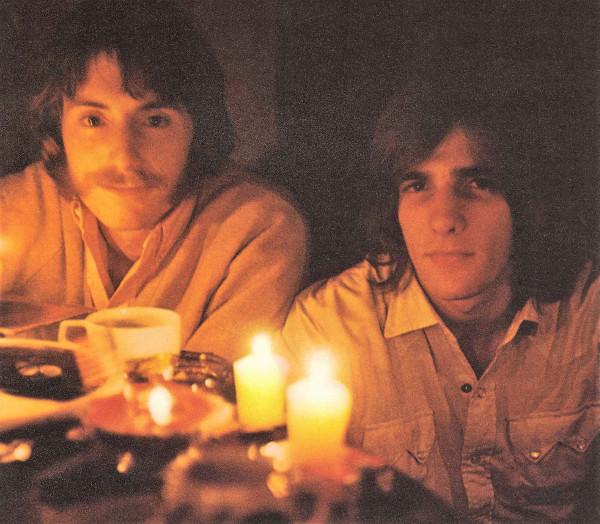

J.D. and I talked about everything and nothing. I had just come from Texas by way of New England, and he was a transplant himself, so we shared stories of home. The conversation flowed naturally, the way it sometimes does when you meet someone who’s just… easy. Later that night, he introduced me to Glenn Frey. Glenn Frey. I didn’t know it then, but I had just been knighted into a circle of rock royalty.

Lucy’s, as the locals will tell you, had this magic. You’d walk in, grab a table, and somehow end up in conversation with a legend. Lucy Casado herself was convinced her restaurant had a special pull, a charm. And sitting there that night, with J.D. Souther and Glenn Frey, it was hard to argue otherwise.

Over the years, I’d run into J.D. here and there—always at Lucy’s or some place like it. He never changed. The world around him would be swirling with fame and frenzy, but J.D. was always J.D., cool and collected, like a stone in a river that doesn’t get swept away. We’d nod at each other from across the room, maybe exchange a few words, but that first night at Lucy’s was the moment we connected, even if it was over a mistaken identity.

He was, of course, so much more than just “the guy who wrote that song for the Eagles.” Souther was the secret weapon behind so many hits, the unsung hero of the Southern California sound. His collaborations were legendary, his songwriting deeply personal, and yet universal in a way that made it feel like he was narrating your life, even when he was singing about his own. He co-wrote songs like Best of My Love, Heartache Tonight, and New Kid in Town—tracks that became the soundtrack to a generation.

J.D. had that rare gift of capturing heartbreak and hope all in one breath. He could take a moment, a feeling, and turn it into something timeless. It wasn’t just music; it was emotion set to melody. And like all great songwriters, he wrote from a place of truth. Even when his songs were filled with pain, there was always a sense that everything would be okay in the end.

It’s funny, thinking back on those early days at Lucy’s, how unaware I was of the musical revolution happening right around me. J.D. Souther, Glenn Frey, Don Henley—these guys were rewriting the rulebook for rock and roll, and I was just trying to get through my first few months as a columnist without getting fired.

But J.D.? J.D. was cool, unbothered by the chaos of fame. He was the guy who could sit in a noisy restaurant, scribbling lyrics on a napkin, while the world outside roared on without him. He didn’t need the spotlight, but the spotlight needed him.

Now, at 78, J.D. Souther is gone. And while the world will remember him for his music, for the songs that shaped a generation, I’ll remember him for that first night at Lucy’s. I’ll remember his kindness, his wit, and that cool, unflappable demeanor. J.D. Souther wasn’t just the new kid in town—he was the guy who made everyone feel like they belonged in this crazy, mixed-up city of angels.

Rest easy, J.D. You were always the coolest guy in the room, whether we knew it or not.

TONY CASTRO, the former award-winning Los Angeles columnist and author, is a writer-at-large and the national political writer for LAMonthly. org. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.