We Don’t Use Ballrooms for Reunions. We Rent the Dallas Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium

My parents came from families big enough to play baseball against one another — and still have players on the bench. One aunt gave birth to 19 children. Another aunt bore 16 sons and daughters. Several aunts had enough children to field football teams. And those were only the legitimate kids my uncles had.

My multi-generational family is a lot like the mythical Buendía clan from Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Bizarre, mystical, eccentric, turbulent. Or like something from The Bible.

When God said, “Be fruitful and multiple,” He may have been talking to my family. One of my aunts gave birth to 19 children. Another aunt bore 16 sons and daughters. Several aunts had enough children to field football teams.

And those were only the legitimate kids my uncles had. Need I add that their children have followed God’s mathematical directive almost as well.

Both my parents, of course, came from families big enough to play baseball against one another — and still have players on the bench. At last count, the number of aunts, uncles, cousins, second cousins, cousins twice removed and so on numbered almost 1,000 scattered across Texas and the Southwest. And that’s just the adults.

My family doesn’t use hotel ballrooms for reunions. We rent the Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium.

But this isn’t a story about the desperate need for birth control in my family. Or about what good Catholics they are. It’s a tale about Hispanics, polls and how Latinos vote when no one is watching.

No one in my extended family has ever been contacted by a pollster, political or otherwise — and this includes multiple generations over more than three quarters of a century involving more than 2,500 registered voters (the others are too young) who are Democrats, Republicans, independents, Green and Communist party members and even a Tea Partier or two.

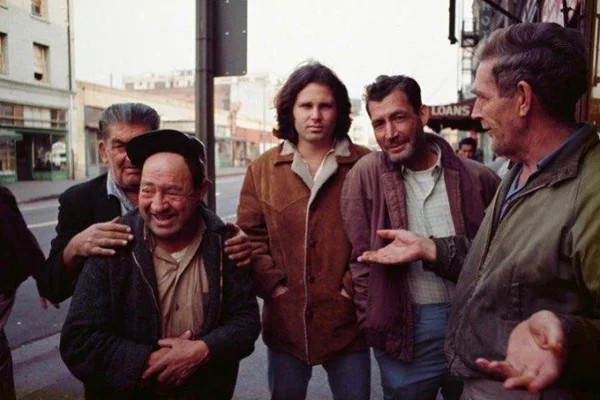

Personal family archives

I also have several thousand friends — real ones, not the Facebook kind — and about 1,500 of those are Latinos. I sent e-mails to almost 1,200 of them recently. Not one of them had ever been contacted by a pollster either or participated in any kind of political survey.

I bring this all up not to boast about the sexual prowess of the men in my family, yours truly excluded, but to make a point about politics and Hispanics — and how some of them vote and are never going to honestly tell complete strangers how they voted nor for whom they voted.

In the 1960s I began traveling across my home state and the Southwest, often inviting myself into the homes of complete strangers, usually for dinner and sometimes overnight. At first I did it while researching a book I wrote. But then I did this as I continued working as a newspaper reporter.

Nothing has ever surprised me of what I have learned from my family and my extensive collection of people who have had me into their homes. Perhaps that’s because I’ve learned that I don’t think my family is altogether different than many Latino families in America with the same backgrounds:

Multiple decades, if not centuries, of living in this country. A strong sense of family and religious values. Generations of service in the military. A disdain for law-breaking. An incredible belief in the American Dream matched by an equally high suspicion of foreigners, even those from what was our distant ancestors’ homelands.

From the experience of my family and several decades of acquainting myself with strangers whose only common bond was that they were Hispanic, I feel comfortable in making some conclusions about the Latino vote that will not be found in traditional polls and studies.

Foremost among those conclusions is to tell anyone who discounts the possibility of Latinos voting for a Hispanic Republican simply on the basis of ethnicity that I offer four words:

Brian Sandoval. Susana Martinez.

They are recent governors of Nevada and New Mexico, two states with high Latino populations, among them some of my relatives. Sandoval and Martinez are Republicans, and they were elected to office in 2010, just two years after Barack Obama carried their states with their increasing Hispanic constituency on his way to the White House.

Sandoval’s Democratic rival in 2010 was the son of one of the state’s magical political names — Nevada Senator Harry Reid, the late former Senate Majority Leader. He also had to battle against the anti-GOP backlash of Arizona’s immigration law. Martinez defeated a career politician with a big campaign war chest and the endorsement of the popular former and late Gov. Bill Richardson, a Latino who had run for president two years earlier.

Shift the talk to presidential politics, though, and a dark queasiness comes over any conversation. Many of them refused to talk at all about President Obama when he was in the White House. My suspicion is that in 2008, less than half my relatives voted for the Democratic candidate, contradicting polls indicating that Obama carried more than two-thirds of the Latino vote nationally.

I don’t know how to explain the disconnect, although my sportswriting colleague Mike Lupica once wrote a political column headlined “The Silent Issue That Could Doom President Obama.”

The issue? Race.

“If there is one great truth about polling in this country, at least when it comes to race, it’s that people lie through their teeth,” Lupica wrote in the New York Daily News. “Mostly because they don’t want to look like some lousy, scummy bigot — even talking to an anonymous voice on the telephone.”

The one thing I learned about all my crash visits with Latinos over the years is that, like my relatives, few of them had any African American friends. They lived in predominantly white communities with almost no African American neighbors, none in Latino barrios. Their children mostly attended private or parochial schools with few, if any, black students.

In many ways, both my relatives and the Hispanics I visited have had far more in common with their Anglo counterparts that people would imagine. They not only are “white” on the U.S. Census forms, they are also acculturated “white” in most respects, even how they feel about race and specifically about African Americans.

Race is, like Lupica said, the issue “that nobody will want to talk about very much in polite society.” But it exists, and this time all the fantasy surrounding Latino-Black relations and the talk about hope and change have disintegrated into a reality of tough times, an economic nightmare and hardball politics.

And my family?

All I can say is that I’m still getting scolded for having invited my mother’s Cuban friend Caridad to my late father’s funeral and to a reception afterwards at my parents’ home. Caridad happens to be Black and a santera to boot.

I don’t know what upset my relatives most — that my mother had a Black friend or being reminded that my mom also practiced Santeria.

Or perhaps it that she gave birth to only two kids.

TONY CASTRO, the former award-winning Los Angeles columnist and author of “Chicano Power” (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is an editor-at-large with the Los Angeles Independent. “Chicano Power” will be republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com. Website: https//tonycastro.com

Photo

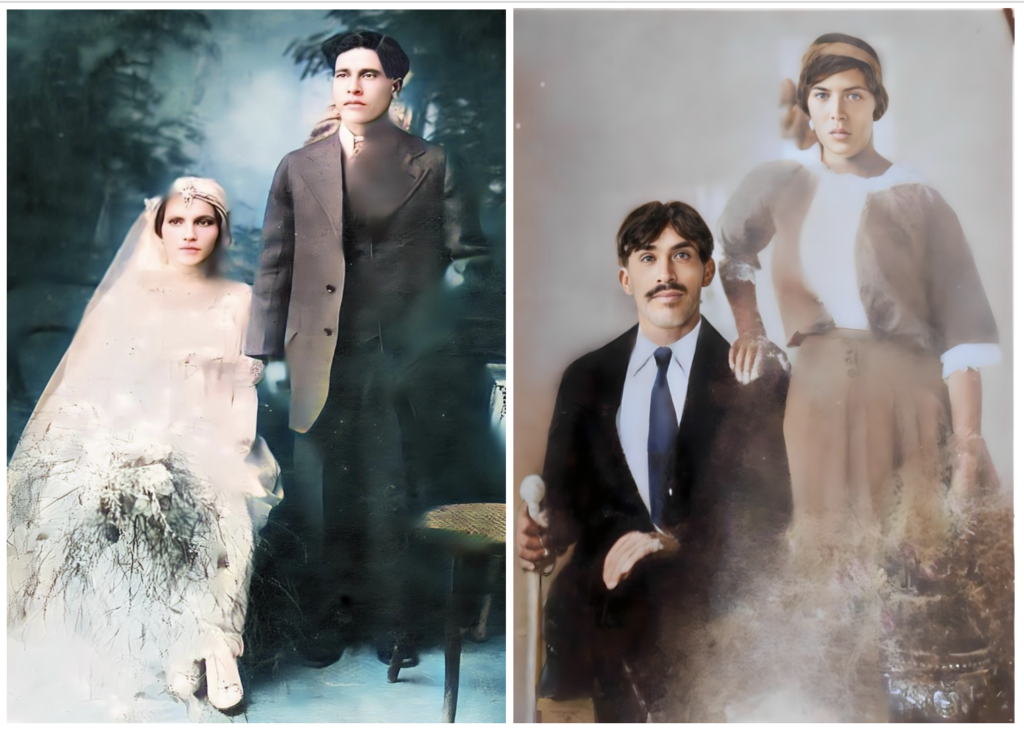

Grandparents.jpg

caption

when

My family’s founders: Concepción Rivera and Reyes Segovia and José Angel Castro and Catalina Guevara.

Personal family archives