They lived in an East L.A. home almost 30 years and then their landlord decided he wanted the house for his growing family.

By ALEJANDRA REYES-VELARDE, CalMatters

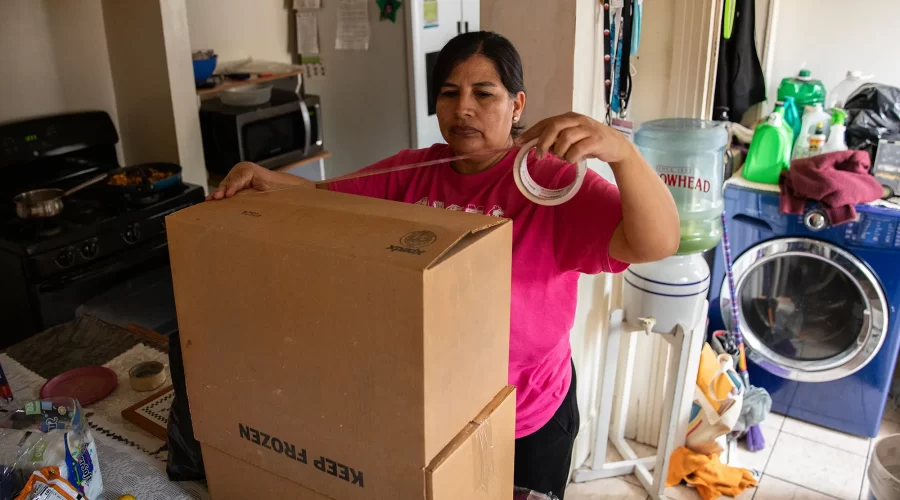

Days before Christmas, María Vela was saying goodbye to the narrow one-bedroom apartment in East L.A. that has been the backdrop of her family’s lives for the last 30 years.

Vela looked at her wedding photo hanging in their living room. The couple hosted their wedding reception out on the driveway, Vela said, gesturing outside. They raised four children in the duplex near the end of a cul-de-sac in their historically Latino neighborhood. Their kids enjoyed a quintessential East L.A. upbringing until one-by-one they left for college, except for Vela’s youngest girl, a high school junior.

Now the family was being evicted by Christmas so their landlords, who live next door, can move in.

Evictions are on the rise nationwide and in California. While most Los Angeles-area evictions happen because tenants struggle to pay rent, even tenants who manage to remain current with rent are at risk of eviction. These “just cause” or “no fault” evictions happen because landlords want to move into their tenants’ units, renovate a unit or leave the rental market.

No-fault evictions are contributing to the displacement of families from their longtime communities, along with other factors such as rising rents, too few affordable units, and expired tenant protections.

Photo by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters

“Homeowner move-ins have been bringing about this exodus of Angelenos leaving their communities because they can no longer afford rent,” said Cinthia Gonzalez, an organizer at Eastside Leadership for Equitable and Accountable Development Strategies (LEADS). “It’s a heavy load.”

After state pandemic-era tenant protections expired, average monthly eviction filings surpassed pre-pandemic levels in a dozen of California’s most populous counties, according to court records obtained by CalMatters.

Counties that extended local eviction moratoria saw delayed, but still stark, eviction increases. That was the case for Los Angeles County, which saw a 17% increase in eviction filings the first eight months of 2023, compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Even though there have been state and local efforts to strengthen protections against evictions for “just cause,” those protections didn’t help Vela’s family stay in their longtime home.

A man who identified himself as one of Vela’s landlords told CalMatters he didn’t want to comment on the matter.

Vela has lived in the same home since she immigrated to the U.S. in 1996.

She met her husband at a party while he was visiting Mexico. Within months they wed and went together to East L.A., where he was already living with his three brothers.

When the brothers came across the duplex unit in the early 1990s, it was dilapidated and littered with trash in a neighborhood with active gangs. The brothers asked the landlord if they could fix it up in exchange for being able to live there. The landlord agreed and charged them $300 monthly.

As the family grew, the home started to feel smaller.

Over the years various landlords neglected the property, Vela said. Walls are chipping, holes where mice have crept in are covered by unsecured wood, and mold grows in the bathroom.

But they were able to remain there long enough to give Vela’s children the stability and joyful upbringing they needed to succeed.

Carolina Correa, 23, graduated from Brown University and landed a job at an environmental justice nonprofit in San Francisco. Diana Correa, 26, graduated from UC Berkeley and is pursuing a master’s degree in history. Jesús Correa, 19, started at UC Merced in the fall.

The youngest, 16-year-old Fabiola Correa, wants to follow in her siblings’ footsteps and become valedictorian or salutatorian at Esteban Torres High School. She’s eyeing UC Berkeley too.

Carolina remembers whispering with her siblings as they lay on bunk beds or on the floor, to not wake her parents in the bedroom. They slept in the living room and another living space in the apartment and had little privacy, but it helped them stay close.

Their father taught them to ride bikes and he’d watch them ride in circles on the dead end street, Carolina said. He hosted carne asada barbecues with family. Block parties with live bands and traditional Mexican food and sweets brought neighbors together.

“It was really nice to just have that literally right in front of my house, on my street, and to be a part of community in a way that is something so special to East L.A.,” Carolina said.

Tina Rosales, an attorney with the Western Center on Law and Poverty, likened the family’s displacement to other times in history when Latinos were moved from their neighborhoods, including the years before Dodger Stadium opened in 1962.

“This is heartbreaking, but it’s not new,” Rosales said. “It’s a trend. As we put more value on homes and people owning property, we tend to displace the communities that have been there forever.”

Rosales is among the attorneys who worked on a tenant protection law recently passed by Gov. Gavin Newsom to close loopholes to “just cause” eviction protections. The law requires owners who move out tenants and then move themselves or family members in to reside there for at least a year. And it will require landlords to pay one month’s rent in relocation assistance.

Tenant advocates pushed for the law because they believe landlords were taking advantage of the rules. Landlords sometimes use owner move-ins as a pretense, Rosales said, when actually they want to put their units back on the market at a higher rent.

“It’s important to balance the interests and needs of both (landlords and tenants) while recognizing that housing is a basic need, and as a society we must prioritize keeping people housed,” said Sen. María Elena Durazo, the Los Angeles Democrat who authored the law. “Market housing is a business, and like in many areas of business, consumer protections are necessary in order to ensure that bad actors out to increase their own profits are not able to take advantage of or abuse the consumer.”

Los Angeles County and city have even stronger just cause protections, but local advocates say even those rules have weak spots.

For instance, in L.A. County landlords or their family members who move into tenants’ units have to live there for three years. If they don’t, the previous tenants have a right to move back in under their original lease terms and rent.

But the law seems to place the burden of keeping track of the landlords on tenants. Javier Beltran, deputy director of the Housing Rights Center in L.A., said he hasn’t heard of a case of a tenant successfully reclaiming their unit because of landlord violations.

“In reality once (tenants) move out, it’s hard to keep up with that particular tenant,” Beltran said. “They probably moved on to a different place, situated themselves and to a certain extent, moved on. It’s hard for them to come back.”

Vela always knew eviction was a possibility. The duplex had been bought and sold multiple times in the last several decades, and each new owner had been willing to keep them as tenants, until now.

Eastside LEADS helped Vela delay her eviction by a year and a half after finding flaws in the landlords’ eviction process. For example, Gonzalez said, the landlords offered less than the required amount for relocation assistance.

But after the organization sent a letter to the landlords, they corrected their mistakes and agreed to pay the $12,688 in relocation assistance the county requires in this case.

Vela has found searching for housing difficult. She and her husband aren’t fluent in English, they are undocumented, and they’ve purchased most of their belongings in cash, which means they don’t have much credit history.

Also the going rents in that neighborhood are sometimes double what they’re paying now, which would be impossible for them to afford on her husband’s meatpacking salary, she said.

At one recent home viewing, Vela brought her daughter Fabiola to translate. The landlord interrogated Fabiola: Did the family have visitors often? Did they party? Were they loud?

Vela left feeling dejected and worried about Fabiola.

Carolina has been trying to help from the Bay Area, where she lives. After work or on her breaks, she finds housing leads and makes phone calls on behalf of her parents. She adds herself and her boyfriend as co-signers, hoping that’ll increase her parents’ chances.

I’ve submitted applications for them to move into places and then burst into tears afterward,” Carolina said. “I want them to get into these places so bad, but because I’m not there I can’t facilitate further. I do what I can and so does my older sister, but it’s difficult.”

Diana, the oldest, feels guilty she hasn’t been able to help as much as she’d like.

“(I was) really angry with myself and with the timing,” Diana said, adding that if the landlords had waited five more years, she could finish her master’s program, start working and pool her money with her siblings to buy their parents a house. “I was like, damn, I’m not ready.”

Recently she created a GoFundMe page hoping friends and community members will help defray the cost of storage units and moving trucks.

Vela said she is coming to grips with the fact that their only option may be to leave East L.A., and maybe Los Angeles altogether. With no immediate home to go to, Vela thought about moving in with her sister in San Bernardino County temporarily while her husband stays in his brother’s El Sereno apartment, closer to his work.

The lack of affordable housing for very poor residents is a major factor in the state’s rising homelessness problem.

Margot Kushel, director of UC San Francisco’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative, said even if this family isn’t immediately homeless after vacating their home, they could be at risk for homelessness in the future.

Kushel’s research on homelessness in California revealed 49% of those without a home had been “non-leaseholders,” usually people staying with friends or family until it isn’t possible anymore. Those living arrangements often are precarious and lead families on a path toward homelessness, Kushel said.

She listed other challenges contributing to people’s vulnerability to homelessness: high deposit fees, moving costs, the impact of moving on peoples’ jobs and personal stability.

A recent law passed to limit what California landlords can charge for security deposits won’t be in effect until next summer, too late for Vela.

Evictions and potential homelessness impact entire families, Kushel said, risking people’s ability to graduate from college or high school and to build wealth in the future.

“Housing is really at the root of thriving,” Kushel said.

The solution is to build more affordable housing far faster than Los Angeles is currently doing, said Stuart Gabriel, a real estate professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. Most investment in housing creation is driven by profit and built by the private sector.

Not everyone purchases property to make a profit, he said. “It’s a very complicated and nuanced story and doesn’t lend itself to easy culprits and easy answers,” he said.

Vela’s family recognizes their landlords probably just want more space for their family. She said the landlords are two siblings who live with their elderly mother.

The family has conflicting feelings about the landlords and their family’s situation.

“It’s complicated for us because they do have a case and we don’t anymore,” Diana said. “I get it. You bought a house. But at the same time you knew we were here.”

Vela’s husband said he’s grateful for the time they were allowed to stay.

“It just so happened that someone bought the house and now we have to leave. But without resentment or anger,” Jesús Correa Cabrera said. “We’ll close the door behind us and say ‘thank you very much.’ And life goes on.”

Within days the family slowly disassembled their East L.A home, packing belongings they’ve accumulated over several decades into black trash bags and cardboard boxes.

Diana, Carolina and young Jesús’s high school class photos, Fabiola’s shelves of books, the quinceañera and wedding photographs, were all taken down.

As Christmas neared, they summoned a sense of hope for the future.

“I feel sad, kind of stressed for my family,” Fabiola said as she sorted a drawer of colored pencils and pens. “But at the same time I feel like we’re going to get out of this and maybe start a new time of our lives. A new beginning.”

The day before the family was preparing to move out, they heard they were approved for an apartment in El Monte, a one-bedroom for $1,700 a month, plus utilities and rental insurance.

It’s far from their community, smaller, and too expensive for them to afford comfortably. But the family said they have no other choice.

Alejandra is a California Divide reporter writing about inequality in Los Angeles. She previously covered breaking news, the pandemic and Latino communities for the Los Angeles Times. He can be reached at newton100@ucla.edu

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. Published with permission of Cal Matters

PHOTO 1

Vela eviction…jpg

Caption

María Vela assembles a cardboard box as her family gets ready to move out of their home of nearly 30 years in East Los Angeles on Dec. 17, 2023.

Photo by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters