The famous but now shuttered Lucy’s El Adobe Café in Hollywood holds a special place in California pop culture but now symbolizes the demise of the Chicano Movement’s once promising political dreams in the Golden State.

By TONY CASTRO

AS THE YEAR 2023 CLOSED OUT, feeling a bit nostalgic about my early days in Los Angeles, I visited the once famous but now shuttered Lucy’s Adobe Café on Melrose Avenue across the street from Paramount Studios. I’m not sure what I was looking for, and what I found maybe belonged on some unused Hollywood backlot, forlorn and forgotten.

In the El Adobe’s glorious day I always entered Lucy’s through the rear. Maybe for that reason, I climbed the wrought iron fence guarding the driveway and made it to the back entrance, just as the skies unleashed another rainstorm. Everything was safely locked, looking as deserted as my friend Patty Casado — the late owners’ only living heir — warned me it would be.

But I hadn’t gone for the margaritas, nor the vegetarian tostadas. I had gone to visit the memories, most of which had to do with my late friend best Alex Jacinto whom I met there in the most extraordinary of ways. The fact that it was extraordinary had nothing to do with either of us. Nor even with the business that brought us together one autumn afternoon at a table in the darkened, near empty side room of the famed Hollywood Mexican restaurant.

Lucy’s Adobe Café had once been among the trendiest restaurants in the city. It had also been famous as the Los Angeles haunt of former Governor Jerry Brown during his first two terms in the 1970s and during his romance with Linda Ronstadt. Less well known was the fact that restaurant owners Frank and Lucy Casado were financial supporters of various aspects of the Chicano movement’s activities and Latino political candidates. Additionally they had been close friends of the movement’s martyr, slain Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar.

Alex Jacinto was the Casados’ lawyer, and he was insistent that Jacinto and I had to meet. His lawyer was about to file a landmark civil rights lawsuit against the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department that was bound to ruffle feathers in the city.

It was 1978, shortly after I had arrived in Los Angeles. In the brief time I had known him, Casado had taken to calling me the “New Kid in Town,” the title of a hit song in the Eagles’ great “Hotel California” album — and the Eagles, the hottest name in music, were regarded as extended family by Casado and his wife Lucy who had fed and sheltered the group’s members during their days as struggling artists.

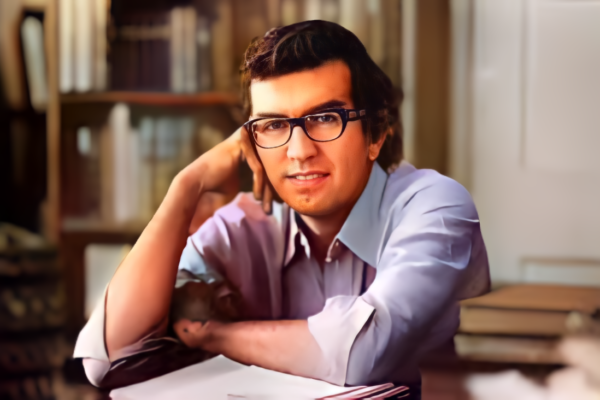

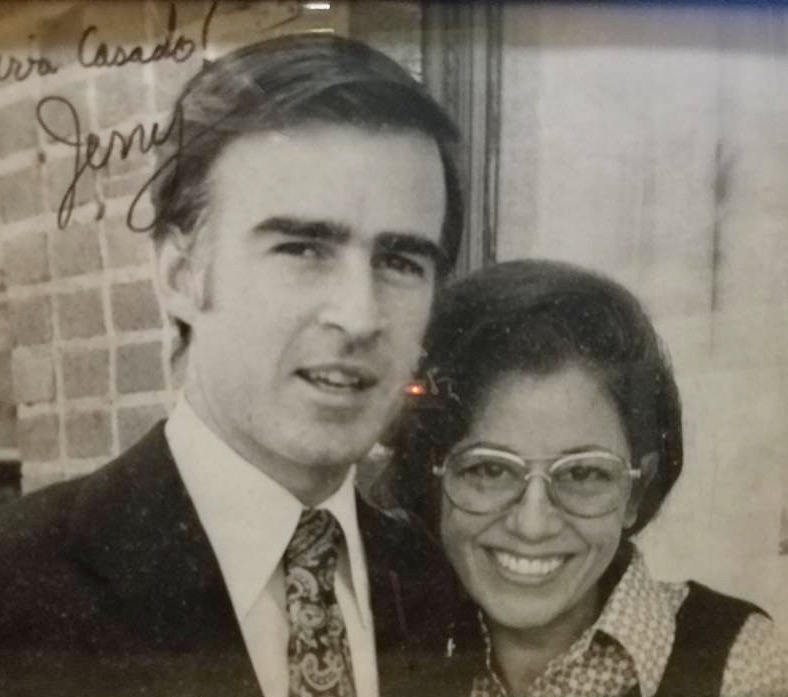

I was the “New Kid” because I had only recently arrived in Tinseltown to write a three-times-a-week column for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, a strike-crippled afternoon newspaper attempting to resurrect itself from near ruin through splashy New Journalism: hiring a big name editor, Jim Bellows, who had given birth to the New Journalism back East, and show-boating aggressive advocacy reporting and columns by journalists like Denis Hamill, the legendary writer Pete Hamill’s younger brother, and myself, the author of a recent bestselling Latino civil rights manifesto titled Chicano Power.

Alex Jacinto reminded me of a larger-than-life Orson Welles stepping out of a scene from the film Citizen Kane. He was as loud as he was big and commanding. As I jogged my memory for where I’d seen Jacinto before, Casado broke the ice with a pitcher of margaritas and a large, inviting plate of a dish called Taquitos Jacinto that he said he had named in honor of Alex: sliced beef steak wrapped inside corn tortillas with rice, beans and guacamole.

“This isn’t Mexican food,” said Casado, whispering so that the only other customers on this side of the restaurant wouldn’t hear. “It’s Tejano food.”

“Is he from Texas?” asked Jacinto, pointing at me, almost accusatory.

“Sure is,” said Casado. “Just like Lucy.”

Jacinto let out a loud laugh as he hung a large napkin from his shirt collar. “Now you’ll have your hands full! If you thought having one Tejana was bad ass enough. Imagine having two around.”

That’s when it got extraordinary.

Our conversation was halted by the thunderous sound of roller skates indoors, echoing loudly –– CUR! CUR! CUR! CUR! Had the Roller Derby come to town? We could hear someone careening through the narrow hallway leading into this side of the restaurant, with the sound growing louder, almost violent. CUR! CUR! CUR! CUR! And what a showstopper. CUR! CUR! A gorgeous, smiling roller-skater caromed into the side room of Lucy’s El Adobe, skate-screeching to a sudden stop and booty blocking our table.

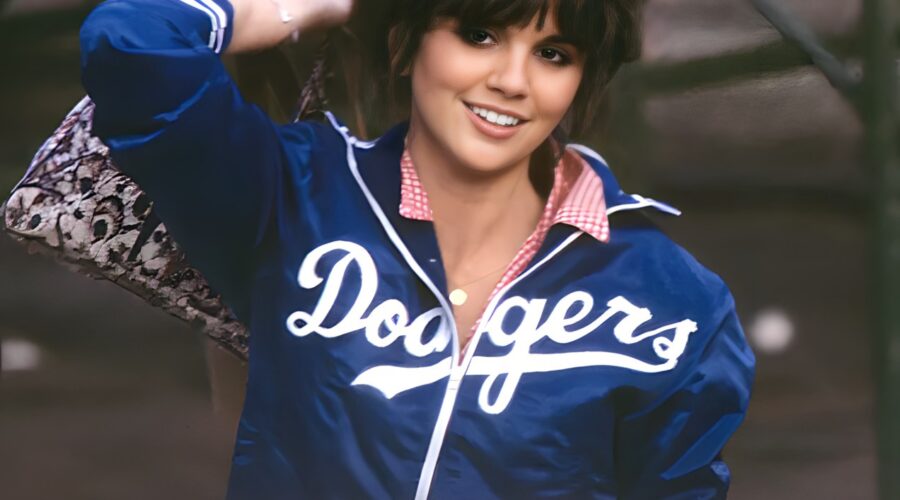

Linda Ronstadt, no less in roller skates and wearing shorts and a Dodgers jacket, gave Casado a big hug and kiss. She looked superstar radiant, just like the night a year earlier when she made a splash singing the national anthem at a World Series game against the New York Yankees at Dodger Stadium. That was such a hit that Ronstadt wore a similar satin jacket –– along with short shorts, kneepads and roller skates –– on the cover of her 1978 album, “Living in the USA.”

Yes, with the exception of the Dodgers jacket, that was what she now wore.

I immediately stood up. Casado noticed and gave me an inconspicuous down-boy wave with his hand.

“You can take the kid out of Texas, but you can’t take manners out of the kid,” said Casado, who, being an unruffled former sailor, acted as if this –– Linda Ronstadt, the reigning queen of rock pecking his cheek –– was an everyday occurrence, and continued puffing on an unfiltered cigarette. Jacinto also kept a nonchalant look that I tried to imitate, though I think my mouth was agape as I sat back down.

“Whacha doin’?” Casado spoke to the rock star as if she were his daughter, Patty, who was, in fact, a close friend of the singer.

“Rehearsing,” said Ronstadt, removing a helmet and shaking a head of beautiful hair. “Back on the road in Texas in December.”

“On the road at Christmas?” asked Casado.

“Just a few dates,” said Ronstadt. “But at The Forum on Christmas Eve. You and Lucy have to come.”

Casado then introduced us to Linda. I had met her briefly several months earlier, but there was no reason she would remember. She held on to Frank’s arm as he got up to take her to the restaurant office, likely for a more private conversation.

They had a backstory that would become an important footnote in political history. Among some in the news media, Casado and his wife were known as Jerry Brown’s surrogate parents, for it was no secret that Brown had a complicated relationship with his father, former Governor Pat Brown. Jerry had never hidden his ambivalence about his back-slapping politician father, and their differences had created mixed feelings. Like his father, the son had been attracted to political office –– but, unlike his father, he was repelled by the gritty work of winning it.

With the Casados, Jerry had filled the holes he had at home. Frank and Lucy had known him since his early entry into politics when he ran for a community college district trusteeship.

Brown often visited the restaurant late at night, staying into the wee hours of the morning talking politics with Casado and spiritualism with Lucy. Then when he was elected governor in 1974, Brown appointed each of them to state boards and commissions.

Two years later, he made a quixotic but late entry into the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination race. He couldn’t stop Jimmy Carter from the nomination, but Jerry Brown’s political ceiling seemed endless. So did his personal capital.

As Brown was finishing his first term as governor, the Casados tried their hand at matchmaking. In an unlikely pop cultural pairing that could only have been scripted in Hollywood, Jerry and Linda became a couple who surprisingly were able to keep their romance secret until early 1978. Their love affair came into full bloom when they celebrated Brown’s 40th birthday at Lucy’s El Adobe while hordes of photographers and television crews waited outside.

I was present at that small birthday party the first week of April, thanks to Casado. I had met Frank and Lucy about a month earlier, just days after arriving in town. They had paid a visit to the publisher of the Herald Examiner, Francis Dale, formerly the publisher of the Cincinnati Enquirer as well as president of the Cincinnati Reds who had helped build the world champion Big Red Machine teams.

The publisher had insisted that I sit in on the meeting with the Casados. After all, I was the Herald Examiner’s new columnist and, more importantly for this meeting, the only Hispanic on the newspaper’s staff. Dale had asked me to come to his office early that day to get acquainted. We both had a lifelong interest in baseball and were memorabilia collectors as well. Among the Reds mementos adorning his office was future Hall of Famer Johnny Bench’s game-used catcher’s mitt, which he allowed me to handle and try on.

“Do a good job for me here at the paper,” he said, “and I’ll leave it to you in my will.” I told him he had a deal.

Moments later, Dale and the Casados were in mildly spirited conversation about politics. Dale was a staunch Republican who served on Richard M. Nixon’s Citizens Committee to Re-Elect the President and became Nixon’s ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva.

The Casados were polar opposite politically. They were not only closely allied with Jerry Brown and Democratic Party but also supporters of numerous Chicano Power civil rights groups and causes. Soon, though, Casado managed to impress upon the conservative publisher that, despite their political differences, they were intimately bonded.

“We’re tocayos, Frank,” said Casado, taking up Dale on his request that he call him that. “I’m Frank, too. And in our culture, two men sharing the same name are called tocayos.”

Frank Dale was letting that swill in his mind and swiveling, as was his habit, in his big executive chair when the most unexpected thing suddenly happened. Dale leaned so far back in his chair that he fell backwards, flipping in geriatric acrobatic fashion and crashing behind his desk with his legs landing on a credenza against a wall.

The Casados and I were stunned and motionless. For a moment I thought my publisher had suffered a heart attack and died. I have to confess. My first fleeting thought was a selfish one: that he hadn’t yet put me in his will giving me his Johnny Bench catcher’s mitt. So I wasted no time in rushing to my publisher’s aid along with Casado.

There was a shocked look in Frank Dale’s eyes. His face was flushed. He was breathing heavily. And he smelled of something strong. Casado and I tried to help him to his feet. I didn’t know Casado yet, but we exchanged a look of recognition, not of each other but of the smell of booze, as Dale apologized profusely..

“Don’t worry about it, Frank,” cracked Casado. “This happens with the margaritas in my place all the time.”

That stormy night I ate at Lucy’s El Adobe for the first time, and the Casados and I got drunk on margaritas laughing about our bizarre afternoon and how their political pow-wow had almost killed the publisher. It was also the rainiest April in the history of Los Angeles, and a few days later Casado helped me move from the Ambassador Hotel, where rain had flooded my bungalow, to the Chateau Marmont, the celebrity hotel packed with Old Hollywood glamour on the Sunset Strip. There, for a few days, my next-door neighbor was Audrey Hepburn. It wasn’t like working at the poor Herald Examiner didn’t have its perks. It was picking up all the bills, and Casado had insisted that I ask to be put up at the Chateau Marmont.

“Heck, if they won’t do it, I’ll call my tocayo Frank Dale myself,” said Casado. “I’m sure he wouldn’t want pictures of him upside down in his office making the rounds.”

“You don’t have photos of that, do you?” I asked, finding it inconceivable that Lucy had the quick presence of mind to surreptitiously snap a picture with a disposable camera of the new Herald Examiner publisher unceremoniously upended in a chair with his legs dangling in the air.

Casado’s sly smile was one for the ages. “No, kid,” he said. “But Frank Dale doesn’t know we don’t.”

“Besides, the Chateau Marmont is where you want to be right now,” he said. “It’s the place not just for big stars but writers, too. A lot of good movies were written there. The Day of the Locust. That was written there. Billy Wilder. He wasn’t too bad, was he? He began his career writing there. It’s also a great place to hide your sins. That guy Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures. Warren Beatty once told me that Harry Cohn used to tell all those bad boys he had under contract, ‘If you have to get into trouble, do it at the Chateau Marmont.’ So, yeah, kid, it’s the perfect place for someone running away from trouble.

“Kid, don’t get me wrong. It’s great having you here. You’re infamous but for all the wrong reasons.”

What Casado meant was my troublesome mound of lawsuits and bills and the stories that had followed me to California. My auto insurance company was suing me for deliberately setting my Porsche on fire in the middle of Harvard Square. Not true. My former Houston landlord was suing me for the damage that my two former roommates, strippers to whom I’d sub-let my apartment, did in almost destroying the place. The lease had expired. A guy in New Orleans was suing me for punching him and breaking his jaw. Self-defense. My ex who left me for a used catheter salesman wanted my royalties for Chicano Power. Good luck with that. A lawyer in Dallas was claiming I’d sold him a defective Snipe sailboat now at the bottom of White Rock Lake. The guy would have sunk Noah’s ark. The line was long.

Casado’s way of helping was feeding me for free, like he and Lucy had done for Linda Ronstadt, the Eagles, Jackson Brown and a litany of music artists.

“They were all young, and they’d all wound up in Los Angeles and many of them were homesick,” said Casado’s daughter, Patty. “They came here when they were stuck or lonely or had writer’s block or just wanted company.” I felt humbled and honored to be included.

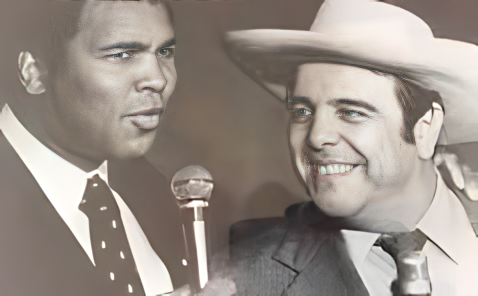

And in Alex Jacinto, I had a good friend and a lawyer who broke the stereotype. He was more Don Quixote than I ever imagined, a modern-day knight errant never shy about jousting with windmills he found offensive to his sense of justice. In 1982, he ran for Los Angeles County Sheriff, challenging the same powerful but corrupt longtime incumbent he had successfully sued in that 1978 civil rights case. In that race Alex became a cause celeb often campaigning with no less than boxing legend Muhammad Ali alongside him.

“I’m supporting Alex Jacinto because I see him as the conscience of Los Angeles,” Ali said in his endorsement. “He is a good, honest, moral man, and I don’t say that lightly.”

Jacinto lost that race, but I sensed that the experience changed him. In the coming years, he became a crusader against abortion, stem cell research and other causes that were dear to his progressive Democratic pals, much to their chagrin. In Mexico City he was so moved by the Virgen de Guadalupe tilma enshrined in the cathedral that he bought an expensive life-size replica that he then carried in the back of his car for religious pilgrimages around southern California.

But the change didn’t spoil his sense of humor, which was uncanny. He once attended a Mardi Gras costume party at my home dressed from head to toe like a Roman Catholic pontiff, replete with the papal mitre, cape, garments and even the red shoes. That night Pope Alex beat out the trapeze-swinging male stripper with a 12-foot python, the boogying John Travolta Saturday Night Fever impersonator, and a sexy bikinied pole dancer for best costume.

All the while, Alex was watching my back.

On one occasion, he kept me from pulling the plug on a Latino hack in the Nixon administration with whom I had often quarreled. My reporting in Houston had exposed that official and others of misusing tens of millions of dollars in federal grants and programs to woo Latino voters in the Southwest for the Nixon re-election campaign.

It was just one of the many Nixon scandals related to Watergate. In the aftermath, a number of Latino officials lost their jobs, some faced criminal prosecution and others like the hack who showed up at Lucy’s El Adobe one night was ruined in politics. Casado knew him in passing and, unaware of our history, brought him to the side room where Alex and I were having dinner.

The hack immediately greeted me with a profanity-laced invective and proceeded to insult the English woman I was with, calling her a “British hussy.” My good manners be damned. I responded by hurling my plate still laden with most of a vegetarian tostada at the former Nixon official.

The plate hit him in the face and then smeared guacamole and salsa over his shirt and suit. Stunned, the guy retreated from the table and called police, demanding that I be arrested for assault.

“Assault! What with? A deadly tostada?” demanded Jacinto when police arrived. “That’s an insult to my client’s restaurant!”

Casado interceded, explained what had happened, and treated the officers to a complimentary dinner. Then he asked the former Nixon official to leave.

“That Castro kid just ordered another margarita,” Casado, who also possessed a wicked sense of humor, told the pol. “Another margarita and who knows what he’ll wind up throwing at you.”

But this was Lucy’s El Adobe, remember, a place that might have been imagined for a Hollywood lot, especially for its margaritas which could be as sedative as the climate. My screenwriter friend Teo Davis called it one of the consummate California destinations for a certain set to go after the sun, the Colombian gold, the Cuervo tequila, and the California blondes had kept you up at the Pacific until dawn with thoughts surfing on a suicidal, if you’ve indulged in enough of a cocaine jag to need three Tuinals to reduce agitation. Then, Teo used to say, Lucy’s was better than the Betty Ford Center in the desert, and much closer.

One night Lucy took me by the hand and introduced me to a handful of her friends who were there: Joni Mitchell, Don Henley, Dolly Parton, Daryl Hannah, Barbra Streisand. On another evening songwriter Jimmy Webb played his famous “MacArthur Park” on the baby grand piano he had given the restaurant, while nearby Secret Service agents checked the surroundings to clear the cafe for a visit by a presidential candidate. Bobby Kennedy had dropped by in 1968 on the afternoon of his last day alive, and many others followed.

But the restaurant had only one favorite son. On the night of the governor’s 40th birthday, April 7, 1978, I was seated with Frank and Lucy at a table adjoining the one where Jerry and Linda dined with Jerry’s mother, father and sister. Jerry was in rare spirits, playful and loving with Linda, gracious to anyone who came to wish him well, cheerful as toasts were offered and as he was serenaded with “Happy Birthday” and “Las Mañanitas,” the traditional Mexican birthday song. And what did the governor have for his birthday dinner at Lucy’s? Well, it wasn’t the arroz con pollo dish that Casado had named the Jerry Brown Special.

“He’s having Taquitos Jacinto,” said Casado. “Steak strips wrapped in corn tortillas with beans and rice. The guy I named it after is sitting over there.”

He pointed to the table against the wall next to where the governor was celebrating. There I recognized the governor’s chief of staff, a bodyguard, a couple of aides, a special adviser and guru, and a guy who was dominating the conversation and seemed to be enjoying every moment.

It was Alex Jacinto.

I spent many New Year’s Eves with Alex and friends at Lucy’s El Adobe, closing out another year singing “Auld Lang Syne.”

Here’s a cup of kindness, my friend.

Tony Castro, the former award winning Los Angeles columnist and author of CHICANO POWER (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is a writer-at-large with LAMonthly.org. CHICANO POWER will be republished in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.

CHICANO POWER 50 Years Reflections is a series of stories critically re-examining the Latino civil rights history of the more than five decades since the advent of the Chicano Movement in Southern California and the LA County Sheriff’s deputy shooting death of famed Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar, which underscored the very social, economic and political inequities and discrimination against Latinos that he railed against in his writing.

In this five-part series, journalist and author Tony Castro offers a powerful interpretation the Chicano Movement from today’s perspective and writes movingly about Latinos continuing their faithful pursuit of the American Dream: their progress amid broken promises and ongoing challenges faced by Latinos in all aspects of life, but especially in politics and in following in Salazar’s footsteps.

In 1978 Castro, author of the civil rights history Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America (Dutton, 1974), succeeded Salazar as the leading Chicano voice in Los Angeles — a city of almost four million of which more than half are Latino — writing a three-times-a-week column for celebrated editor Jim Bellows‘ Los Angeles Herald Examiner and quickly becoming an influential community figure. (Publishers Weekly acclaimed Chicano Power as “brilliant… a valuable contribution to the understanding of our time.”)

In these stories of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Castro invites readers into the world of Latinos — his world — chronicling the experiences about race, culture, identity, and belonging that have shaped those who led the Chicano movement campaign for human rights and social justice. As much as this story is about adversity, it is also about tremendous resilience. And Castro pulls back the curtain and opens up about his career and personal life — and his struggles balancing himself in a society discriminating against so many like him, and his journey toward open heartedness.

Castro, a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, was a Headliners Club–winning journalist for his reporting on the Latino civil rights movement in the Southwest for the Washington Post, the Dallas Morning News, and the Dallas PBS affiliate KERA’s Peabody Award winning show Newsroom created by the late Jim Lehrer. While a Nieman Fellow, Castro lectured on the Chicano Movement at Harvard’s JFK Institute of Politics and taught one of the first college courses in America on Chicano Studies,

Castro was among the first reporters in America to write extensively about race in presidential politics, as far back as his undergraduate days at Baylor when he reported on Bobby Kennedy’s quixotic 1968 campaign in the Mexican Americans barrios of California, which became a centerpiece of his book Chicano Power.

Castro reported on the civil wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua in both English and Spanish for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and La Opinión de Los Angeles.

The impact of the Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections perhaps can best be explained by a telephone conversation that series writer Tony Castro had with Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano on October 4, just days after Part 3 of the series was posted online. Mr. Arellano and Mr. Castro were acquainted with one another’s careers but had never spoken to each other until this call from Mr. Arellano. Numerous people had brought this series to his attention, Mr. Arellano said, and he had just finished reading the most recent two parts. “It’s absolutely fascinating — and I don’t say that lightly ,” said Mr. Arellano, who was graciously complimentary.

What especially impressed him, Mr. Arellano said, was the depth of Mr. Castro’s behind-the-scenes knowledge of the Chicano Movement, and particularly the Los Angeles political aspects of that civil rights history. Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections, he said, has created an ongoing dialogue and debate among Latinos in the city reflecting a newly heightened frustration among two generations of Angeleno Latinos with their leadership, both past and present. Mr. Arellano’s own background and extensive experience was in Orange County, having only begun writing about Los Angeles for the Times in recent years. So he had found the series especially enlightening and helpful.

It was also Mr. Arellano’s opinion that the biggest impact of Mr. Castro’s series was in showing how Los Angeles Latino political corruption and scandals of the past two generations had failed the city’s increasingly growing Latino community — and how the Latino politicos’ own failures legislatively and politically may have been largely responsible for how Black political power in Los Angeles has continued to exceed that of Latinos, even as Latinos today far outnumber the declining African American population in the city.

Mr. Arellano believed there was incredible irony in that. In late 2021 three Latino members of the Los Angeles City Council along with the Latino leader of the county’s most influential organized labor group held a clandestine meeting to strategize on how to increase the disappointingly poor level of Latino political power in the city. Unfortunately, that meeting degenerated into a shocking racist diatribe with hateful views about black political leaders, their families and even their children. Unbeknown to those in the meeting, their session had been secretly tape-recorded. Almost a year later, an audio tape recording of the meeting was made public in an anonymous social media post in the fall of 2022, causing what has been described as the biggest racial-ethnic political scandal in Los Angeles history.

The fallout was unprecedented. The president of the Los Angeles City Council, a Latina who had been the most vocal in the racist comments, resigned almost immediately. The Latino director of the county Federation of Labor was forced to step down. A second Latino City Council member involved in the meeting soon left office, as he had earlier lost his reelection campaign. A third Latino councilmember has weathered a recall attempt as well as a yearlong campaign by critics urging him to resign. Even President Joe Biden has called upon him to resign. His fate will be decided by voters in a city election later this year.

And it appears that yet another impact of Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections is that it has prompted the Los Angeles Times to undertake a similar multi-part series of its own, re-examining the very same questions about the apparently failed leadership of Latino political power in Los Angeles over the last two generations. According to Mr. Arellano, that series is expected be published later in 2024.

Castro, a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, is also the author of the landmark Latino civil rights history Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America (E.P. Dutton, 1974) that Publishers Weekly acclaimed as “brilliant… a valuable contribution to the understanding of our time.” The book will be published in a commemorative 50th anniversary edition this fall.