On Aug. 29, 1970, the National Chicano Moratorium in East Los Angeles protested the disproportionately high casualties among Latinos in Vietnam — but led to the tragic police shooting death of acclaimed Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar.

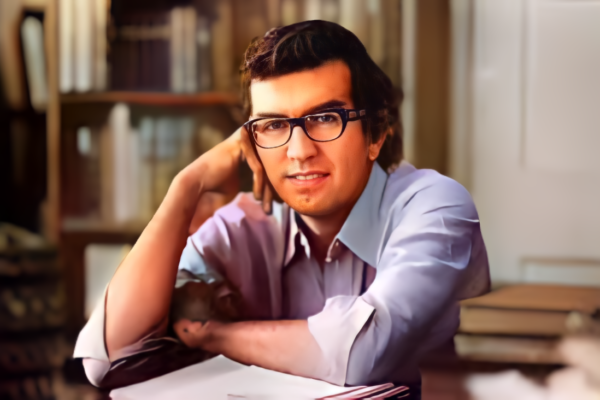

By TONY CASTRO

August 29, 2023

I HAD BEEN IN LOS ANGELES only a few days in 1978 when the unique pressures on Chicano journalists in this city first began weighing heavily on me, fittingly perhaps, in a bar at the Ambassador Hotel, where I was living at the time, not far from the kitchen pantry where Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

Frank Del Olmo, by then the veteran Los Angeles Times reporter I had known since the early 1970s, was welcoming me to his town over drinks and conversation that inevitably turned to the man by whose standard both of us would ultimately be judged. Los Angeles still had two daily newspapers, though barely. The Los Angeles Herald Examiner had recently settled a labor strike whose impact would kill it a decade later.

The Herald Examiner had also hired the editor acclaimed as the greatest in America — Jim Bellows, the editor who in the 1960s had unleashed Tom Wolfe and the New Journalism. And Bellows now had brought me to L.A. to write about the Golden State’s rising political star governor, Jerry Brown, who wanted to be president of the United States, and whose girlfriend was the hot darling of rock ‘n’ roll, Linda Ronstadt. And I’m to do this as a columnist at the near-bankrupt flagship newspaper of publishing legend William Randolph Hearst, whose granddaughter — kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst — was still in prison for a crazy bank robbery, all symbolic of the calamity of the wealth and power and dreams going wrong in California.

Del Olmo wanted to know what the “new” Herald Examiner was really like. Was it everything I thought it would be? It was a chicken-shit question, so I gave him an answer that was deservingly half-truthful and just to make conversation with someone I didn’t completely trust.

“Frank,” I said, “I’ve been working full-time as a reporter on daily newspapers since 1965, since I was eighteen, and I don’t mean as some lackey L.A. Times intern fetching coffee and carbon paper, and I authored a pretty damn good civil rights book — so I took this job because I thought they were hiring me, that they wanted me, the experienced reporter and feature writer, not because I happened to have been born Mexican American.

“But when I got here, Editor Jim Bellows and the executive editor told me, without pulling any punches, that they wanted me to be Ruben Salazar. They wanted me to follow in his footsteps, which is kind of flattering but completely unrealistic, don’t you think? I’m not entirely sure they even know what Ruben was writing in those years when he was raising hell with his column. Plain and simple, they were hiring me because I’m Mexican American. I could just as well be a caddy from the Riviera Country Club, you know?”

Del Olmo smiled somewhat uncomfortably into his drink. “Too bad. But I guess there’s a lot of people who expect us to be Ruben Salazar. What did you say?”

“I told them, `I don’t want to be Ruben Salazar — Ruben Salazar got his ass shot off! Besides, I said, I’m not sure a Ruben Salazar is what Los Angeles needs any more. I told them that instead of a Ruben Salazar at the Herald Examiner, what the paper needs is about five more Mexican American reporters and a couple of Mexican American editors. Now that blew them away. Of course, they’re not going to do anything like that. And I’m fucking disappointed. I should have told them to fuck off and gone to work at the Texas Observer where no one pulls any punches with upper class niceties.”

“Why didn’t you?”

“Somehow I got a damn Porsche out of this, and it’s keeping me out of the East where I almost froze to death a year ago.”

“You make yourself sound like a sell-out.” Del Olmo was loving all this.

“I am a sell-out, Frank. I’m just not naïve enough to think I’m the only sell-out sitting here. We’ve got a long way to go before either of us is in the class of Ruben Salazar. And we’ve got a longer way to go before there’s any meaning for his death.”

In a bar across town eight years earlier, Salazar had been killed — assassinated, some activists believe — at the height of his fame and notoriety as the most controversial Chicano journalist of all time. Salazar, in fact, became the martyr that the then-floundering Chicano movement needed to extend its life. In Del Olmo, of course, I was preaching to the choir. Our entire careers, it seemed at times, had been lived in the shadow of Ruben Salazar. Frank would live a lifetime with the expectations of being another Salazar, and, ultimately, I hope he made peace with both the expectations and the ghost that had thrust itself upon him, taking it all to his grave in 2004.

The day after having drinks with Del Olmo, my editor at the Herald Examiner and I had lunch with a group of the so-called movers and shakers of East Los Angeles. I would meet for the first time most of the city’s Mexican American political and economic power brokers. It was a meeting that Bellows and the publisher should have been taking for the purpose of some meaningful dialog. By having me there, though, it offered a distraction. But I was, after all, part of the revived Herald Examiner’s showpieces. It also turned into a book signing event with Bellows taking great pride and joy that I had signed on to help in resurrecting the paper.

Someone from the group we met with brought several dozen copies of Chicano Power for me to sign. The book had become the scholarly benchmark in Chicano Studies programs at colleges and universities in California and throughout the country, while for others it was a page-turning political manifesto that helped fuel the Chicano movement in America. I had been graced with the validation of a coveted journalism fellowship at Harvard. And I was credited with having exposed Richard Nixon’s campaign dirty tricks against Hispanics, which had been a footnote in the sordid Watergate scandal. After the meeting, a couple of those Eastside movers and shakers took me aside and began detailing the agenda they had in store for me. When I asked them what they were talking about, one of them looked me eye to eye.

“You,” he said, “have to carry on the work that Ruben Salazar began.”

I cringed and began looking for ways to get out of L.A.

Several months later, now checked into the Chateau Marmont Hotel, I was approached by a young screenwriter named Stephanie Liss who was developing a screenplay for the actor Henry Darrow, a New York-born Puerto Rican actor who had risen to fame playing Manolito Montoya on the 1967-71 NBC television western series The High Chaparral. It didn’t take long, however, to figure out that the screenwriter was writing a fictitious account of the Ruben Salazar story and apparently wasn’t getting much assistance from Salazar’s family or friends in “fleshing out” the main character.

“I need your help,” she said, “because Frank Casado says you’re the closest thing I’ll find to what Ruben Salazar was like.”

“I don’t think Frank really knows who I am,” I said.

“He says you’re a loose cannon seething full of anger and frustration and that your writing drips with emotion. He says you are Ruben Salazar whether you want to accept it or not and that you can help me with my screenplay.”

I laughed. “I think Frank is just worried I’ll write a negative column about his restaurant,” I said. “Or that I’ll run off with his daughter.”

That night I confronted Casado, the Hollywood restaurateur who had been one of Ruben Salazar’s best friends and whom I had become close to in my short time in Los Angeles.

“Don’t be mad at me, kid,” said Casado. “Ruben didn’t want to be who he was either. But he didn’t have any choice.”

In the following years, hardly a week went by when Salazar wasn’t thrown up to me, sometimes as a compliment but more often as a knock, the way some wayward son might have the reputation of a dead father rubbed in his face. I hadn’t set out to become a Chicano columnist, a term that I never applied to myself but which both Chicanos and non-Chicanos seemed determined to place on me. I hadn’t ever thought of myself as being very Chicano. And I wasn’t too comfortable with the title columnist either. I saw myself as a reporter who had fallen into the role of a columnist and, to some degree, I suppose, into the role of a Chicano as well.

From time to time, I found myself having long conversations with people who had known Salazar, especially Casado, whose Lucy’s El Adobe Cafe in Hollywood had been only a short walk for Ruben from the Spanish-language station KMEX-TV where he worked the last year of his life. I dared not tell anyone that I had, in fact, spoken with Ruben in 1970, just weeks before his death. At the time I was a young reporter at the Dallas Times Herald. There, an assistant city editor who had reported from Vietnam with Salazar thought I should meet him and put us together on the telephone.

“You need to be in L.A.,” Ruben said to me. “Come to L.A. I’ll get you on at the Times, and you can help me kick butt here.”

I was flattered, but I was barely out of Baylor University, and I had goals of going to the East Coast, not the West Coast. A week or so later, Ruben even stopped in at the Dallas Times Herald newsroom to visit with his war correspondent buddy. Ruben and I then conversed almost entirely in Spanish in the middle of the newsroom, an unusual sight indeed. At the time I was the only Latino reporter working on any major Texas daily. Suddenly to see the two of us in the same newsroom conversing in a language no one else understood must have seemed threatening, especially given the rise of the Chicano movement throughout Texas and the Southwest. In the weeks and months that followed, colleagues and editors began to raise questions about my close personal relationship with leaders of both the Chicano movement and the New Left.

By then, too, it had become common knowledge among my colleagues that I had skirted the U.S. embargo of Cuba to tour Fidel Castro’s communist citadel with two of the most notorious 1960s New Left groups in America, the national Students for a Democratic Society and the South Texas-based Mexican American Youth Organization, better known by its acronym MAYO.

So, among some of my colleagues and editors in conservative Dallas, I had unwittingly gained the reputation of being a New Left activist, if not a communist. It didn’t help, I supposed, that I was often having lunch with United Workers Auto labor boss Pancho Medrano. Before my senior year in high school, I had worked all summer in my uncle’s Dallas construction business and had gotten to know Medrano who was a partner. Four years later, I’d accompanied Pancho to Los Angeles where he spent the California Presidential Primary trolling the East Los Angeles precincts for Bobby Kennedy’s campaign. I wrote about the experience for my hometown weekly, the Waco Citizen, and then included the reporting in writing Chicano Power. I was in Los Angeles on the night that Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel, but I was at a United Farm Workers’ party watching the tragedy unfold on local television.

I was twenty-one, exhilarated one minute, shocked and exhausted the next. Politics and violence, worlds we’d come to know in national tragedies — President Kennedy in 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. two months earlier in 1968, and now Bobby Kennedy — had become uncomfortably interwoven into the American fabric. You had come to expect it. Or at least I did. Perhaps that is why I wasn’t shocked by what happened to Ruben Salazar just three weeks after our meeting in Dallas. It wasn’t out of character for a country still moving on fumes from the 1960s.

On Aug. 29, 1970, some 25,000 activists gathered in East Los Angeles to take part in what was billed as the National Chicano Moratorium march and protest against the Vietnam War. They were protesting the disproportionately large number of Latino soldiers who were being killed in Vietnam. It never occurred to any of them that one of three people who would be killed that day as a result of the march would be perhaps the most important Latino who would die in the age of civil rights protests.

Ruben Salazar, a controversial crusader for Latino rights — especially against law enforcement — was slain when Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies fired a tear gas projectile into an East L.A. bar that struck him in the head, killing him instantly. Salazar was also news director at KMEX, L.A.’s pioneering Spanish-language television station. No one was ever arrested — then or since — in connection with Salazar’s violent death. Although no action was taken against those involved in his death, Los Angeles County did pay $700,000 to Salazar’s family to settle a wrongful-death lawsuit.

Was I bothered about what had happened to Ruben? Damn right I was. Could I do anything about it now eight years later? Not likely. Protests and demonstrations in the 1970s and into the new millennium produced new inquests, but nothing came of it. No one was prosecuted or even charged. To me, the real question was what had Salazar’s longtime powerful, influential employer — the Los Angeles Times with all its gloried history and clout — done behind-the-scenes, not just in preening with empty editorial copy, to secure justice for him? That failure right there showed the true might of the press in California, or lack of it, against an entrenched political power structure of which it was an integral part.

I often argued with Del Olmos over this very point. I would emphasize what Frank himself had often said, that even his mother who lived in the San Fernando Valley refused to subscribe to the Times. Yet he couldn’t find his way to seeing how it was as much his oppressor as his employer. Finally, in 1994, Frank publicly threatened to resign when the Times endorsed conservative Republican Governor Pete Wilson for a second term in office, despite his support for the anti-immigrant ballot measure, Proposition 187. Del Olmo, though, couldn’t do it. Then Editor Shelby Coffey III talked him into taking a two-week vacation to “think about it.” Tantrum over, Del Olmo wrote a dissenting opinion piece lambasting Wilson and Proposition 187. It was like putting lipstick on a pig. The Times got to keep its Latino figurehead, and Del Olmo retained his title and position in the city. His impact was negligible. Wilson was re-elected to a second term, and voters overwhelmingly passed the ballot initiative establishing a new citizenship screening system that stopped undocumented immigrants from using non-emergency health care, public education, and other services in the state.

“I hope you think I put up a good fight,” Del Olmo said the next time we met.

“Frank,” I said, “when it comes to symbolism, you’re the champ.”

Back in 1972 I had called Frank just a few months before a much-anticipated, long-ballyhooed Raza Unida national convention in El Paso to introduce myself and to arrange to meet there. We were both the same age, from the same socio-economic backgrounds, and virtually alone in covering the same stories. Over dinner and drinks, we also learned we had one other important thing in common: We were each married to lovely blonde, blue-eyed women. However, as we drank and talked more freely, I came to understand that Frank was troubled beyond belief that he had married a non-Latina. He spoke about the disapproving looks he would get, especially from Latinas his own age, making him feel that he was responsible for having badly depleted the bank of eligible Mexican American men with good futures ahead of them.

Didn’t I get those same looks, too, he wondered. Maybe I did, I said, but I didn’t pay any attention to them. My personal life was none of their business, I told Frank. Neither should his be, but I sensed that Frank’s issues were more deeply rooted than what people thought of him. I also joked about how I was more concerned about the possible lynch mobs of white men angry that I’d married a beautiful Anglo woman, which he didn’t think was funny. Frank, I came to understand, especially as I got to know him in the years ahead, had no sense of humor on this subject. He asked more than once if I felt guilty not having married a Latina. I would have felt insulted except that he quickly informed me that he was often guilt-ridden and uncertain if the marriage would last.

“You really don’t feel guilty?” he wanted to know.

“I don’t understand,” I said. “Why should there be any guilt. You married the woman you fell in love with and a woman you love, didn’t you?”

Frank, though, feared there had been some kind of heritage betrayal on our part. By marrying non-Hispanics, he wondered whether we might be engendering an entirely new race of people and diluting the existing Mexican American bloodlines that had been created from the original mestizo process — the mixing of Spaniard and Mexican. We strongly disagreed, and we had words, not kind ones either. It was also obvious that we saw ourselves and our roles as journalists differently. Frank was in the process of organizing a group of Hispanic journalists in California as a kind of informal Chicano journalists union and wondered if I was interested in trying to do the same in Texas. Absolutely not, I said.

“Frank, I don’t see myself as a Hispanic or Mexican American journalist,” I said. “I see myself as a journalist, period.”

“Well, you’re being naïve,” he said. “Others see you as that.”

“That’s their problem,” I said. “I can’t control that, but I’ll be damned if I allow how they look upon me or treat me to affect the way I see myself or the way I behave professionally. You start branding yourself a Chicano journalist, and you’ve lost. You’ve allowed those people whose hearts and minds you want to change to get into your own head. This isn’t like joining a guild or a union. You do this and you start advocating for something as a Chicano, and guess what? You’re not much more than another activist, just one with a byline.”

Nevertheless, at the time I actually wanted to share a byline with Frank. Chicano Power was becoming an overwhelming undertaking. As La Raza Unida’s convention in El Paso showed, the movement was rife with fractionalization and rivalries, not only along state lines but also as to priorities. To do justice, it would require extensive reporting in California, New Mexico, and Colorado as well as Texas. Despite our personal differences, I proposed to Frank that he handle the two westernmost states and I would cover Texas and New Mexico, as well as do the writing. But Frank resisted. He didn’t like the idea of a book written about the movement from a dispassionate perspective. The issues, he said, were too important not to take sides and get involved. I agreed and, if we were activists, we should jump in without hesitation. But we weren’t. I wasn’t, at least. I would do the book on my own, getting a tremendous assist from Roy Aarons, the West Coast bureau chief of the Washington Post,who to that time had done perhaps the best reporting on Cesar Chavez and the farm workers as well as the Chicano movement in California. Aarons helped open doors with Chavez at his compound in La Paz especially and guided me through the occasionally hazardous trail of interviewing other movement leaders in the Southwest.

I also came to find Del Olmo almost Pollyannaish in believing that dramatic change in California and in the country was, if not imminent, then certainly almost at hand, and he had an unfounded confidence that the Los Angeles Times would be instrumental in achieving that new society. On the other hand, I believed that our children would be fortunate to see that transformation, which I didn’t see occurring for at least a generation, maybe two. Our previous generation would have to die and ours perhaps, too, before we would see significant social change. Frank’s optimism, I felt, came from being a native Californian and influenced from living so close to the source of where so much change had begun in the past. But it was often a change that, while reported nationally, would never be widely implemented or accepted outside of California and parts of the East Coast. My pessimism, if it were that, stemmed from being a Tejano who had witnessed widespread resistance to social change and had grown up in a largely white environment where racism and discrimination weren’t as politely dished out as I found to be the case in California. Neither the Herald Examiner nor the Times were exemplars of champions or activists for civil rights. All we had to do was look at the newspapers’ mastheads and the list of their newsroom and editorial management from which Latinos, African Americans, and Asians were largely excluded.

“How can you be so negative about the future?” Frank demanded to know.

“I’m not negative,” I said. “I’m realistic. Pero no les pinto los labios a esos cochinos — I just don’t put lipstick on those pigs. They know what I am, and I know what they are.”

I was a pain in the butt. I admit it. From the time I was young, I’d been called all kinds of names based on my ethnicity or the color of my skin or my heritage or native language. Usually, there was nothing I could do about it. That changed when I began working in newspapers. I had punched out two fellow reporters at papers where I was a reporter, and I came close to slugging an editor at the Herald Examiner. Yeah, I could be a violent son-of-a-bitch. Not especially proud of it, but prouder than being the chicken shit racists I leveled. Hell, it was Texas. I knew reporters who carried handguns into the newsroom. I was capable of terrible things, but I chose to fight the hatred into which I was born. So my frame of reference on our world was different than that of the gentle, civilized Del Olmo.

As a young intern at the Times in 1970, Del Olmo’s fate was molded by Ruben’s violent death. He hardly knew Salazar, a veteran reporter whose controversial columns in the Times exposing inequities and injustices against Latinos had exalted him to hero status in the city’s Mexican American communities. But Del Olmo would be traumatized as if Salazar had been his next of kin. In a journalistic sense, he was. Soon Del Olmo was made a full-time reporter on a newspaper that had virtually no Latino presence on its staff. A cub newspaperman, he was thrown into a situation reluctantly following in Salazar’s footsteps, without either the experience or the swashbuckling style that had marked Salazar’s tenure.

At the time I was a reporter covering civil rights at the Dallas Times Herald, which in the summer of 1970 was bought by the Los Angeles Times. On the day the deal was announced, Otis Chandler, the publisher of the Times between 1960 and 1980, attended the news conference in Dallas. Physically, he may have been the most impressive and imposing newspaper publisher to ever appear in public. At forty-three, he looked like an Olympian god: blond, golden tanned skin, 6-foot, 3 inches and 220 pounds, a former record-breaking shot putter at Stanford who was kept out of representing the U.S. in the 1952 Olympics by a wrist injury. The afternoon after buying the Times Herald, Chandler made a dramatic appearance in our newsroom. Dressed in a cream-colored suit, he personally introduced himself to each editorial staff member. Heck, our own publisher had never done that.

A month later, Ruben Salazar was dead, and Del Olmo and I began commiserating about the loss in phone conversations and in that long El Paso weekend binge of tequila and regret. The regret that we both had was having been thrown into the coverage of Latino issues by virtue not of any special skills other than being the only Spanish-speaking Latino reporters on our respective staffs.

“I don’t think of myself as a token — and I don’t think I am a token,” I recall him lamenting. “But why do I feel that that’s how I’m looked at by many of my fellow reporters and editors?”

I sensed a tortured soul residing within Del Olmo, far more consumed with race, ethnicity, and inferiority than anything I had felt, and I had often brooded on all of that too much for my own good. A part of Frank made me feel shallow. A part made me feel sorry. A part made me curious as to what ghosts of American ethnic uncertainty haunted him. Several years passed before I spent any more significant time with Frank. When I moved to Los Angeles in 1978 to go to work as a columnist for the afternoon rival of the Times, Frank was not only among the first to welcome me but also tried to help me understand the ethnic-cultural landmines confronting any Latino journalist in the city. Several years later, we spent a few weeks together in El Salvador reporting on that country’s civil war and again commiserating on the personal war within each of us.

I soon came to realize that Del Olmo had at long last developed a love-hate relationship with the Times. At various times, he and the growing legion of Latino reporters he had helped recruit to the paper were on the outs with the editors. Once he and another Latino reporter came to me almost in tears, upset that a city editor had become so infuriated with their surprise confrontation of a Times executive editor at a Chicano News Media Association gathering, that the next morning he had called Frank on his office phone extension and demanded that he “round up your Mexicans and get in here!” Could I write a column about that? I did, and we only succeeded in pissing off my editors as well as those at the Times.

It may have been Del Olmo’s ultimate payback that he later was able to successfully lobby for a special reporting and editing team for a comprehensive series on Latinos that in 1984 won a prestigious Pulitzer Prize gold medal for meritorious public service for the Times. When I congratulated him, I jokingly said, “Man, Frank, you sure rounded up your Mexicans, didn’t you?”

From time to time, we would put differences aside and tilt margarita glasses at Lucy’s El Adobe. Once we sat at a booth with Edward James Olmos alternately pleading and berating us over our reporting. Frank, being much more serious and conscientious about such matters, patiently heard out Eddie. I got up and left. I couldn’t take the life that we had both chosen as seriously as Del Olmo did, at least not seriously enough to be lectured to by an actor. At Lucy’s one day, I pointed to a poster of what I presumed to be Manolete, the famous Spanish matador known for his gaunt, severe demeanor.

“Frank,” I said. “That guy was a great matador, but he didn’t look like he was having very much fun living.”

“Yeah, well, I’ll take Manolete.” Frank said it like it was a curse.

I was having an early dinner with Lucy Casado, the owner of Lucy’s El Adobe on the afternoon of February 19, 2004, when a friend called her restaurant to tell her that Del Olmo had collapsed at his office at the Times and died of an apparent heart attack. He was fifty-five.

We were both shocked and didn’t know what to say for a moment.

“I promised Frank that I would dance on his grave if he died before I did,” I said after a while.

“What did he say?” Lucy asked.

“Don’t do me any favors.”

I did, and from time to time I would take flowers to his grave and continue our conversation. Sometimes I would simply toast him with a margarita at Lucy’s El Adobe, just because he disliked the place so much. He never would tell me why, but I suspect it was because Frank Casado was so often on his case.

“What the fuck’s the matter with that guy?” Casado would often begin, bitching at me as if I knew. “He’s the senior Mexican American at the goddamn Los Angeles Times, and he’s afraid to raise a little hell. What does he think they’re going to do to the Mexican American who succeeded Ruben Salazar? Fire him? Get rid of him? Look the other way when something happens to him like what happened to Ruben. It can’t happen again. These aren’t puppies.”

The shadow of Ruben Salazar was indeed long.

Once, after unloading my soul to him over margaritas about the frustrations of being a columnist who happened to be Mexican American — especially trying to do that in Ruben Salazar’s old stomping ground — Casado began crying.

“Kid,” he said, “this is deja vu. Ruben used to sit in the same chair you’re sitting in, and he used to say the same things you’re telling me now. He felt like a man trapped in the middle. The Chicanos were pulling on him from one side, and the Anglo editors he worked for were pulling on him from the other side. He used to say he felt like a man who was being ripped apart.”

Then one day, out of the clear blue, I received an unexpected call from Sally Salazar, Ruben’s widow, to whom I had written a long letter several weeks earlier.

“There were times,” she said, “when I wanted Ruben to simply walk away — to just walk away from everything that was pressing in on him. I used to tell him, `Ruben, walk away from it before it kills you.’

“And if he had lived, I think he would have.”

Not long after talking to Sally Salazar, I took the advice she had given her husband.

I walked away, thanking Ruben Salazar for each step I took.

Tony Castro, the former award winning Los Angeles columnist and author of CHICANO POWER (E.P. Dutton, 1974), is a writer-at-large with LAMonthly.org. CHICANO POWER will be published in a 50th anniversary edition in 2024. He can be reached at tony@tonycastro.com.

CHICANO POWER 50 Years Reflections is a series of stories critically re-examining the Latino civil rights history of the more than five decades since the advent of the Chicano Movement in Southern California and the LA County Sheriff’s deputy shooting death of famed Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar, which underscored the very social, economic and political inequities and discrimination against Latinos that he railed against in his writing.

In this five-part series, journalist and author Tony Castro offers a powerful interpretation the Chicano Movement from today’s perspective and writes movingly about Latinos continuing their faithful pursuit of the American Dream: their progress amid broken promises and ongoing challenges faced by Latinos in all aspects of life, but especially in politics and in following in Salazar’s footsteps.

In 1978 Castro, author of the civil rights history Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America (Dutton, 1974), succeeded Salazar as the leading Chicano voice in Los Angeles — a city of almost four million of which more than half are Latino — writing a three-times-a-week column for celebrated editor Jim Bellows‘ Los Angeles Herald Examiner and quickly becoming an influential community figure. (Publishers Weekly acclaimed Chicano Power as “brilliant… a valuable contribution to the understanding of our time.”)

In these stories of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Castro invites readers into the world of Latinos — his world — chronicling the experiences about race, culture, identity, and belonging that have shaped those who led the Chicano movement campaign for human rights and social justice. As much as this story is about adversity, it is also about tremendous resilience. And Castro pulls back the curtain and opens up about his career and personal life — and his struggles balancing himself in a society discriminating against so many like him, and his journey toward open heartedness.

Castro, a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, was a Headliners Club–winning journalist for his reporting on the Latino civil rights movement in the Southwest for the Washington Post, the Dallas Morning News, and the Dallas PBS affiliate KERA’s Peabody Award winning show Newsroom created by the late Jim Lehrer. While a Nieman Fellow, Castro lectured on the Chicano Movement at Harvard’s JFK Institute of Politics and taught one of the first college courses in America on Chicano Studies,

Castro was among the first reporters in America to write extensively about race in presidential politics, as far back as his undergraduate days at Baylor when he reported on Bobby Kennedy’s quixotic 1968 campaign in the Mexican Americans barrios of California, which became a centerpiece of his book Chicano Power.

Castro reported on the civil wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua in both English and Spanish for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and La Opinión de Los Angeles.

The impact of the Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections perhaps can best be explained by a telephone conversation that series writer Tony Castro had with Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano on October 4, just days after Part 3 of the series was posted online. Mr. Arellano and Mr. Castro were acquainted with one another’s careers but had never spoken to each other until this call from Mr. Arellano. Numerous people had brought this series to his attention, Mr. Arellano said, and he had just finished reading the most recent two parts. “It’s absolutely fascinating — and I don’t say that lightly ,” said Mr. Arellano, who was graciously complimentary.

What especially impressed him, Mr. Arellano said, was the depth of Mr. Castro’s behind-the-scenes knowledge of the Chicano Movement, and particularly the Los Angeles political aspects of that civil rights history. Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections, he said, has created an ongoing dialogue and debate among Latinos in the city reflecting a newly heightened frustration among two generations of Angeleno Latinos with their leadership, both past and present. Mr. Arellano’s own background and extensive experience was in Orange County, having only begun writing about Los Angeles for the Times in recent years. So he had found the series especially enlightening and helpful.

It was also Mr. Arellano’s opinion that the biggest impact of Mr. Castro’s series was in showing how Los Angeles Latino political corruption and scandals of the past two generations had failed the city’s increasingly growing Latino community — and how the Latino politicos’ own failures legislatively and politically may have been largely responsible for how Black political power in Los Angeles has continued to exceed that of Latinos, even as Latinos today far outnumber the declining African American population in the city.

Mr. Arellano believed there was incredible irony in that. In late 2021 three Latino members of the Los Angeles City Council along with the Latino leader of the county’s most influential organized labor group held a clandestine meeting to strategize on how to increase the disappointingly poor level of Latino political power in the city. Unfortunately, that meeting degenerated into a shocking racist diatribe with hateful views about black political leaders, their families and even their children. Unbeknown to those in the meeting, their session had been secretly tape-recorded. Almost a year later, an audio tape recording of the meeting was made public in an anonymous social media post in the fall of 2022, causing what has been described as the biggest racial-ethnic political scandal in Los Angeles history.

The fallout was unprecedented. The president of the Los Angeles City Council, a Latina who had been the most vocal in the racist comments, resigned almost immediately. The Latino director of the county Federation of Labor was forced to step down. A second Latino City Council member involved in the meeting soon left office, as he had earlier lost his reelection campaign. A third Latino councilmember has weathered a recall attempt as well as a yearlong campaign by critics urging him to resign. Even President Joe Biden has called upon him to resign. His fate will be decided by voters in a city election later this year.

And it appears that yet another impact of Chicano Power Fifty Years Reflections is that it has prompted the Los Angeles Times to undertake a similar multi-part series of its own, re-examining the very same questions about the apparently failed leadership of Latino political power in Los Angeles over the last two generations. According to Mr. Arellano, that series is expected be published later in 2024.

Castro, a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, is also the author of the landmark Latino civil rights history Chicano Power: The Emergence of Mexican America (E.P. Dutton, 1974) that Publishers Weekly acclaimed as “brilliant… a valuable contribution to the understanding of our time.” The book will be published in a commemorative 50th anniversary edition this fall.