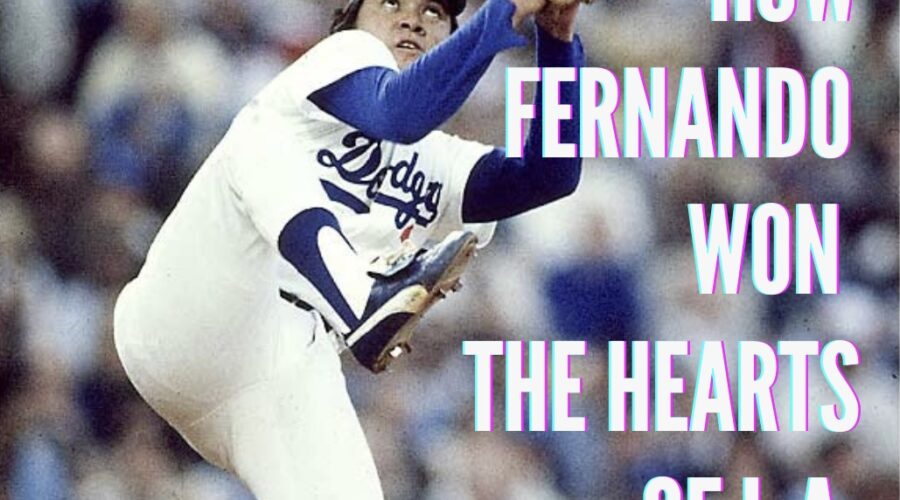

Fernandomania became a cultural phenomenon in 1980s Los Angeles as a young Mexican left-hander became the toast of the city and ultimately a Tinseltown icon as big as any matinee Idol. Fernando Valenzuela had his uniform number 34 retired August 11.

By Tony Castro

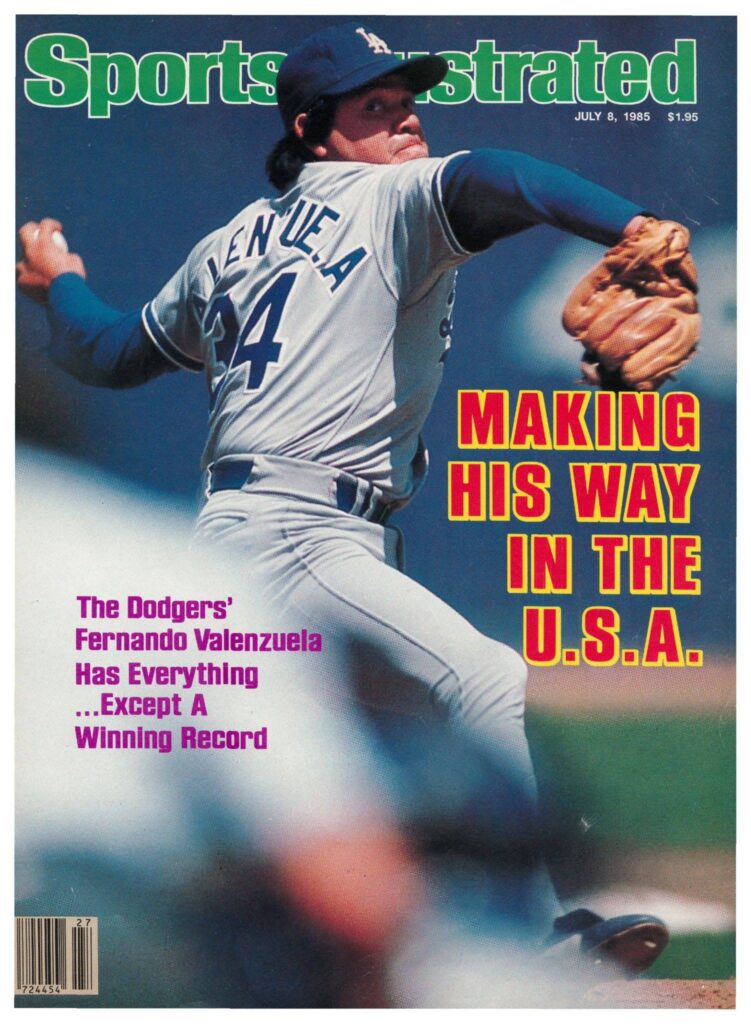

Originally published in Sports Illustrated, July 8, 1985. Republished with permission and courtesy of Sports Illustrated.

FERNANDO VALENZUELA’S LEFT ARM was bent up in an awkward angle, and his hand circled over his wrist as if rhythmically stirring some upside-down concoction. Twirling at the end of his reach was a cowboy lasso in an oblong loop that for a moment resembled a slightly off-center halo. Suddenly, the lasso snaked just above the floor of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ clubhouse and snagged the passing leg of catcher Mike Scioscia.

A few moments later, Valenzuela headed for the playing field, where he saw Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda preparing to sing for an NBC-TV camera crew. Valenzuela shook his head and smiled with disbelief, and when Lasorda actually began piping We Are the World on behalf of the USA for Africa campaign, Valenzuela darted for the outfield, the palms of his hands pressed to his ears.

After the game began, Valenzuela and fellow lefthander Steve Howe spent two innings as Dodger bat boys, sitting in the designated chairs outside the team dugout and retrieving bats from home plate.

Valenzuela’s straight-faced explanation later: “I want to make any contribution I can to help the team.”

Valenzuela’s disarming sense of humor is one of the few ways the Dodgers can smile through the frustration of their season to date. It has been particularly disappointing for the 24-year-old Valenzuela, the 1981 Cy Young Award winner and Rookie of the Year, whose rite of passage from phenom to established star continues to be tested by a running streak of tough luck.

The acknowledged ace of the staff, he may be the best lefthander in baseball, though you could never tell it from his record. He was well below .500 last year (12-17) and he has been struggling to reach .500 this season. Unfortunately, when Valenzuela takes the mound, the Dodger hitters frequently take the day off. Valenzuela the practical joker has been able to make light of it. When the drought was at its worst, Valenzuela was asked to recall the last time his teammates scored six runs for him. “They gave me five in San Diego and one in San Francisco. That adds up to six.”

Ad-libs are not out of the ordinary for Valenzuela. One could see him on the Carson show trading barbs with fill-in Joan Rivers, if only he…if only he…could say all those things in English. There’s the rub, for if Valenzuela still seems to be a charming adolescent with his youthful innocence intact, it may be because the negative adult realities of life haven’t been fully interpreted for him.

Valenzuela was the National League’s Pitcher of the Month in April. He opened the season with a string of 41‚Öì innings without allowing an earned run, breaking Hooks Wiltse’s 73-year-old major league record, and had an 0.21 ERA for the month. Shades of April 1981, when the rookie Valenzuela won all five of his starts—four by shutouts—and had an 0.20 ERA. But the déj√† vu stopped there. Valenzuela’s record for April was 2-3, making him the first Pitcher of the Month with a losing record. The Dodgers scored only eight runs in his five starts, and five came in one game. It was the same story a year ago when the Dodgers scored two runs or fewer in 18 of Valenzuela’s 34 starts. And it goes on.

With three shutouts this season, Valenzuela’s career total is 21. In all likelihood, no other pitcher in history had as many shutouts at his age. “What makes Fernando the great pitcher that he is,” says Lasorda, “is that he has the baseball aptitude of an Einstein.”

His record this year is only 7-8, despite the fact that Valenzuela himself feels he is throwing his legendary screwball as well as he did in his rookie season. “If I am a better pitcher than I was in ’81, and I think I am,” he says, “it’s because of my control.” Physically, the 5’11” Valenzuela more closely resembles his rookie form—even though he is listed at 195 pounds, he weighs close to 220.

Some of his losses this year have been particularly tough to take. In one April game, Valenzuela pitched a two-hitter but lost 1-0 when San Diego outfielder Tony Gwynn slammed a one-out, ninth-inning homer. Walking off the field, Valenzuela first acknowledged a standing ovation with a wave of his glove. Two steps later, at the lip of the Dodger dugout, he flung both his glove and cap at the team bench.

For the most part, though, Valenzuela has maintained his sense of humor and displayed commendable class. But he remains a very enigmatic figure. No sports superstar in this country has ever been interviewed so singularly through an interpreter. The “Americanization” of foreign athletes who have become millionaires in America has always included their braving the language. Look at Ballesteros and Navratilova. But here, a continuing language and cultural gap between Valenzuela and American society has left him in many ways as mysterious as a $1.2 million-a-year player today as he was as an unknown prodigy in 1980.

“I know who I am,” says Valenzuela. “But, yes, sometimes I guess I do wonder if the Fernando Valenzuela that people think they know is the same Fernando Valenzuela that I know. I suppose there are people who expect me to throw a tantrum or to say things—things that you say when you’re frustrated and then later regret—but that’s not the way I am and that’s not the way I feel. I don’t enjoy losing, and I expect to win each time I pitch. But I am not so consumed with winning that I think of it as a life-or-death thing.”

Then, still in the Spanish which he uses almost exclusively, Valenzuela suggested why he might be taking the frustration of the last two years with almost saintly self-control: “I think also that having a family now makes it easier to leave behind any game frustrations at the stadium.”

Valenzuela, who married the former Linda Burgos after his rookie season, is the father of two sons. Fernando Jr. will be three in September, and Ricardo is 16 months old. Both were born in the U.S., making them American citizens. The family lives in a three-bedroom condominium with a panoramic view of the city in a fashionable downtown high rise. Their taste is elegant and expensive. Linda, 24, a former elementary school teacher in Mexico, is partial to Louis Vuitton leather goods and fashions that appear to have just spilled off the pages of Italian Vogue. Valenzuela owns his share of tailored European slacks, tasseled Yuppie loafers and a diamond-encrusted gold Rolex. The condo has a full-time nanny for the boys and an arcade-size Pac Man machine for Valenzuela, a skilled videogame player.

“I’m a homebody by nature,” says Valenzuela. “When the team is home, I may not leave the stadium until midnight or later. Linda and I maybe will have a late dinner, and by the time we get to sleep, it’s even later. Unless there’s a business appointment or something like that, I’ll sleep late, play with the kids for a while and then it’s back to the stadium.”

Valenzuela takes the short ride to Dodger Stadium in complete comfort. He drives a silver Corvette replete with reflectorized, personalized license plates that are de rigueur for a Los Angeles celebrity — FV 34.

He is a long way from Etchohuaquila, his home village in the Mexican state of Sonora. It is a tiny place about 350 miles south of the Arizona border. The reporters who first explored Valenzuela’s origins during the Fernandomania frenzy of 1981 often heard in the nearby Mexican city of Ciudad Obregón that Etchohuaquila was “about 20 miles south—and about 50 years back.”

Three years ago Valenzuela built his parents a luxurious home that has been described as standing out “like a Hearst Castle of Etchohuaquila.” Until then, the village appeared to be no more than a collection of thatch-roofed adobe huts, several hundred villagers and a pitcher’s mound and rubber that distinguished a baseball lot from the garbanzo and sunflower fields. Valenzuela, the youngest of 12 children born to Avelino and Hermenegilda Anguamea de Valenzuela, quit school in the sixth grade and was virtually self-taught on that mound.

Sometimes in the off-season Valenzuela goes out there and pitches to one of his six brothers. All of them still play for Etchohuaquila. The family tends a few acres of farmland under a government program that pays 2,000 pesos a month, roughly $90 in U.S. currency. Some of Valenzuela’s five sisters work as domestics in Ciudad Obregón.

“I’m still as close to my family as I’ve always been,” says Valenzuela. “I still call them after every game I pitch.”

Fernando, Linda and their children split the off-season between Etchohuaquila, where they share the rambling, red-roofed “castle” with Valenzuela’s extended family, and Linda’s hometown of Mérida in the Yucatan, where they were married on Dec. 29, 1981.

“Our spending so much time with our families in Mexico is a luxury we won’t have as soon as the boys are old enough to go to school,” says Linda. “We haven’t decided yet how we will handle their schooling. We’re not uncomfortable here. In fact, there isn’t as much acclimating or assimilating to life in Los Angeles because it is not felt to be that different from life in Mexico. For instance, the language. Spanish is spoken almost everywhere we go.”

Perhaps Linda Valenzuela’s summation of how life for them in Los Angeles differs so little from that in Mexico goes to the heart of answering a question asked often by English-speaking Dodger fans. Why hasn’t Valenzuela completely crossed the language bridge? The answer is simple: He hasn’t had to, in large part because of his good fortune of living in a city with a Spanish heritage. Valenzuela’s public reluctance to use his English seems to be appreciated by Hispanics, for whom the Spanish language has been a historic cornerstone of both pride and discrimination.

“Valenzuela has filled a void that has long existed for a Mexican or Mexican American sports hero in Los Angeles,” notes Ray Gonzales, who as community-affairs director of KTLA-TV follows Hispanic developments in Los Angeles. “What’s also important is that there is the feeling [among Hispanics] that Valenzuela has succeeded without selling out.”

Valenzuela has studied the English language sporadically, attending some of the English classes the team provides during spring training for its Latin players and working off and on with English lessons on cassettes. In the past, most of his postgame comments to reporters were given in Spanish and then translated by Dodger Spanish network broadcaster Jaime Jarrin.

Valenzuela is trying to close the language gap, though, and after he struck out 14 in beating Houston 6-3 on June 22, he conducted his most extensive post-game press conference in English to date.

The transcript:

Q. How did you feel about the five runs your teammates provided in the fifth?

A. Very comfortable.

Q. Did you feel tired when [pitching coach] Ron Perranoski went out to talk to you during the eighth inning?

A. I felt O.K.

Q. Why did you strike out so many in this particular game?

A. I don’t know. But maybe it was because of my control. When I have my control, I stay ahead of hitters. Then I get strikeouts. In the last two games, I’ve felt very good. I’ve been throwing my curveball for strikes. I’ve been working more on my curveball.

Q. Was that the best you’ve pitched this year?

A. Yes, that was the best I’ve pitched.

Valenzuela appeared noticeably self-conscious, but his English, though bearing a heavy accent, was understandable.

In fact, Valenzuela understands quite a bit more English than he lets on. In spring training a year ago, league umpire supervisor Ed Vargo visited the Dodgers’ Florida camp to lecture pitchers on what constituted a balk. Vargo used Valenzuela’s move to first base as an example, but he mistakenly referred to him several times as “Orlando.” When Valenzuela finally stepped forward to correct him, he surprised even his teammates.

“Mr. Vargo,” he said, “I am not ‘Orlando.’ I am ‘Tampa.’ “

“That tells you both how much English Fernando knows and how quick his wit can be,” says Jarrin. “Fernando is just afraid that because he is still not comfortable in English, that he might say something the wrong way.”

Valenzuela, too, has never forgotten an embarrassing incident that occurred at a spring training English class in 1980. Barely 19 and less than a year out of the Mexican leagues, Valenzuela was so shy he would only smile at the instructor when she called upon him. The day’s lesson was a simple drill on phrases used in ordering breakfast. When the instructor insisted that Valenzuela reply, Dodger minor league instructor Chico Fernandez leaned over and whispered an answer in the trusting youngster’s ear.

“Taco,” answered Valenzuela.

The room, filled mostly with veterans, broke up laughing. Valenzuela left the class and never returned.

That incident also offers a hint of both Valenzuela’s shyness and his occasional fits of moodiness. In his first couple of seasons with the Dodgers, he holed up in his hotel room on road trips and spent his time sleeping and watching television. When he stepped out, it was for lunch with Jarrin, broadcaster Rene Cardenas or the two men who have been almost surrogate fathers to Valenzuela—Dodger scout Mike Brito and agent Antonio De Marco.

Brito, a 50-year-old Cuban with a penchant for Panama hats, flashy clothes and home-country cigars, is credited with having discovered Valenzuela as a 17-year-old in the Mexican leagues, which he scouts for the Dodgers. The Dodgers bought Valenzuela’s contract from Puebla for a reported $120,000 in 1979.

Valenzuela’s closest and most influential friend is De Marco, an entertainment producer and film distributor who emigrated from Mexico the year Valenzuela was born. A former actor, De Marco has the good looks of an aging but distinguished movie star, with connections to match. He worked on Ronald Reagan’s first political campaign in California. In 1981, at the height of the Fernandomania craze created by Valenzuela’s 8-0 rookie start, both Valenzuela and De Marco were President Reagan’s guests at a White House luncheon for the then Mexican President Jose Lopez Portillo.

“Fernando’s work comes first — mine second,” says De Marco. “When I took Fernando on as my client, I decided the best thing to do for his image would be for me to get completely out of politics — and I did.”

Valenzuela refers to him as Se√±nor De Marco and says their friendship was further bonded during his controversial 1982 holdout, which both the Dodgers and the Los Angeles news media blamed on De Marco. The agent remains sensitive about the personal criticism he took during the holdout. He savored some vindication in 1983 when he won an arbitration case that made Valenzuela the Dodgers’ first million-dollar-a-year player. Valenzuela, who will be eligible for free agency after the 1986 season, has received a $100,000 raise each of the last two seasons.

De Marco is especially cautious about the Valenzuelas’ safety. He will not allow the family to be interviewed or photographed at home and tries to keep their address secret.

“Fernando is more than just business—he is like family,” says De Marco. In fact, De Marco is godfather to Ricardo, and the Valenzuelas are the godparents of De Marco’s 2-year-old granddaughter, Christine.

De Marco has been equally protective of Valenzuela’s merchandising image by steadfastly insisting that “no chilis, tamales, guacamole, enchiladas or cervezas” will be associated with his client. “I don’t want him to be the stereotyped Mexican,” says De Marco, who must wince at the sight of Valenzuela with a beer in hand at his postgame press conferences. “All offers being equal, he’ll always go for the American name, the American product. Mexican products are different. He’ll always get a great share of that action.”

De Marco’s influence on Valenzuela extends even to the car he bought. While Valenzuela’s teammates suggested that he buy a Mercedes-Benz or even a Rolls-Royce, De Marco schooled Valenzuela about the problems in the U.S. auto industry and how his purchase of an American-made car would be a positive symbolic gesture.

Moreover, De Marco has sought to carefully tailor Valenzuela’s image along the lines of a storybook hero. A fruit juice television commercial showed Valenzuela with some American children. He appears with Julio Iglesias and Placido Domingo in the Spanish version of the We Are the World video, entitled Cantaré, Cantaràs,” to aid the starving children in Latin America. He now spends one day during each home stand visiting elementary schools, mostly in low-income Hispanic areas of Los Angeles where the school dropout rate is as high as 50%, delivering what he calls “my best pitch: ‘Stay in school.’ “

A recent Valenzuela visit to Sharp Elementary in the San Fernando Valley took on the appearance of a fiesta with Mexican music and banners, as the parents and relatives of the children crowded the schoolyard just to catch a glimpse of him.

Wearing the school’s red jacket given to him by the children, Valenzuela passed out large photo pins imprinted with his likeness and his stay-in-school slogan. Students with perfect attendance, he announced, would be his guests at both a Dodger game and at a special dinner with him and his family.

“Tell me again,” he asked over a speaker, “what’s my best pitch?” He asked twice more until the children’s response drowned him out:

“Be smart! Stay in school!”

Valenzuela’s later visit to Florence Elementary almost got out of control when a large crowd of adults mobbed him as he was trying to leave. Women fought to get near enough to kiss him or be photographed with him, while others shoved any piece of paper they could find—including driver’s licenses and utility bills—in front of him for an autograph. To these people, mostly immigrants, and some of them in the U.S. illegally, Valenzuela and his rags-to-riches story legitimize the age-old immigrant dream.

“I’m flattered at having the privilege of being a role model,” he says. “Yes, it’s a serious responsibility. But it’s a responsibility that I can best live up to by pitching as well as I can and hoping that it’s enough of a contribution for us to win.”

To that end, fans send Valenzuela religious relics, including water from Lourdes. Pictures of La Virgen de Guadalupe are tacked above Valenzuela’s locker. A gold medallion of the Madonna and Child hangs on a thin chain around his neck.

Ensconced as an icon of the public, Valenzuela is the Dodgers’ prayer from the cursed fate of mediocrity. And his name still holds magic. To help publicize a downtown-redevelopment project, Valenzuela was asked to put one of his baseball gloves in a time capsule to be sealed until 2085.

“They want a glove?” asked Valenzuela, somewhat dubious. He had been playing with Ricardo in his arms but now put him down.

De Marco explained the concept of a time capsule. “It will not be opened for a hundred years,” he said. “There’s a little bit of immortality there, I guess.”

“And they want a glove?” Valenzuela asked again.

De Marco seemed to finally understand some of the hesitancy.

“Well, Fernando,” he said, “I think it can be one of your gloves that you’ve used in practice.”

Valenzuela was willing to part with one of those.

“Bueno,” he said. Then he smiled and playfully tilted his head from side to side, a bit proud at the thought of a hundred years of glory.

PHOTOS

Photos published with permission of sports illustrated. Cover photo by Jerry Wachter

Republished with permission and courtesy of Sports Illustrated.

Artwork by Bill Purdom shot from personally owned painting.

Fernando by Bill Purdom.jpg

Fernando and Eunissis.jpg

caption

Fernando Valenzuela receives the City Council Proclamation declaring August 11 Fernando Valenzuela Day in Los Angeles from Councilwoman Eunissis Hernandez.

Photo courtesy of the City of Los Angeles

P—HOTO

PETER READ MILLER

The children’s hearts went out to the Baby Bull on his visit to the Russell School.

PHOTO

PETER READ MILLER

Fernando’s hideaway is at home with wife Linda and sons Ricardo and Fernando Jr.

PHOTO

RANDY TAYLOR/SYGMA

Valenzuela and his family spend much of the off-season in this palatial home that he built for his parents in tiny Etchohuaquila

PHOTO

PETER READ MILLER

After Valenzuela left the Astros tongue-tied in a 14-strikeout victory, he conducted his first extensive interviews in English.

PHOTO

RICHARD MACKSON

Fernando went down in history by putting his glove in a time capsule.

JULY 08, 1985